EZTV and the digital arts (anglais)

Michael Masucci, 2025

INTRODUCTION

For full disclosure and transparency, this article is best described as autoethnography. I claim no objectivity. I have had some part in all of the projects discussed here, either as a curator, programmer, creator, producer, or participant. This was, and continues to be, the nature of EZTV. Several “core members,” besides founder John Dorr, each paved their own curatorial and production aesthetics as well as techniques. This resulted in several simultaneous yet separate movements, one leading to me being named by Dorr in 1986, along with him, as “Co-Artistic Directors.”

Since EZTV Video Gallery opened in 1983, computer art, animation, experiments with the internet, and interactivity have always been present. This continued to develop and grow until, by the early 1990s, it became a dominant focus for the space. Projects at EZTV since 1994 included early website creation, massive-scale video projection mapping, and, more recently, holography and experiments with quantum computing. These can all trace their roots to the early works created, curated, and advocated for by artists at EZTV during the period in West Hollywood from 1983-94.

NOTE: Although I am first and foremost concerned with the artists and the work they created, we cannot separate them from the concurrent history of the technology used.

Unlike filmmakers, digital artists often created, or at least modified, the tools they used.

EZTV 1979-94: a Digital Arts Timeline

By the late 1970s, artists had been creating digital images for several decades. These were mainly still images, often printed onto paper, or photographed off screens and then printed. The ability to create moving images was still rare, usually filmed, or else output to video.

In 1979, as John Dorr was experimenting with analog Betamax video1 in West Hollywood, I was in New York combining 8-bit computers, such as the Atari 800,2 and an Atari video synthesizer,3 with video production switchers, cameras, and a ¾” U-Matic video recorder.4 With this hot-rodded technology, and by writing some very simple computer graphics programs in Atari BASIC,5 I created a series of videos called “Standing Waves”.6 Abstract in nature, these real-time animations screened at clubs, including in Los Angeles.

I met Dorr in early ‘83. He told me about the unique video gallery he was planning to open later that year. I immediately joined EZTV as one of its founding members.

At the time, there were few places to see moving images created on computers. There was the SIGGRAPH7 Conference, and occasional exhibitions at museums, universities and galleries. But most commonly, they could only be found projected as electronic light shows at nightclubs. What later became known as “Raves.”

The role that clubs played in digital art cannot be overstated. In addition to music, with the growth of electronica, sampling, and what would become known as EDM, ambient, trance, dub, and drum & bass, early video projectors were being incorporated into larger clubs. And almost every club was equipped with multiple video monitors throughout their spaces. There was a vibrant intersection between Queer culture and various music and fashion genres that frequented these clubs. This created an alternative cultural underground that ranged from punk to disco. And digital imagery was welcomed.

Ron Hays8 (1945-91) was by far the dominant artist presenting electronic video/digital hybrids in clubs in Los Angeles. We had a deep mutual respect, and he helped me a great deal in my early career. Like many artists, Ron was HIV+, and as with many others at the time, and many founding members at EZTV, including John Dorr, Hays, was lost to AIDS.

Several other EZTV founding members, including Patricia Miller, Pat Evans, Earl Miller & Dan Silva, were also interested in computers. We exchanged information and ideas.

In late 1983, Evans suggested I attach an Atari 800XL9 computer to an Atari 103010 modem. I then began posting “EZTV a la Mode(m)”, a BBS,11 an early online presence. In 1984, I curated EZTV’s first one-person show on computer art, Leslie Wilson’s “Cyber Tapestry”.

Early Attempts at Interactive Narrative Cinema

In 1984, EZTV founding member Ron Resnick demonstrated what was hoped to be a soon-to-be-released technology, an interactive laserdisc/keyboard controller by a company called RDI Halcyon.12 RDI expected that their technology would revolutionize narrative storytelling by incorporating multiple versions of scenes, storylines, and finales onto an interactive laserdisc.13 The director would shoot several versions of a feature, and the audience could then experience multiple versions of the story by making choices at various points in the movie. The technology failed commercially. Decades later, similar approaches have been attempted on computers, cable, and streaming TV services.

A crossover between the abstract electronic work seen at clubs and more mainstream cinema, art, and festival environments slowly developed. When EZTV presented an evening of work at the American Film Institute (AFI)14 (in March of 1984, Dorr included Standing Waves in the program, along with excerpts from several narrative features.

15 years later, Majia Beeton,15 who directed the AFI’s first digital program, honored EZTV with a 20th anniversary retrospective.16 EZTV was hailed as “among the core pioneers and advocates of digital technology in the moving image arts.” That event began with a prerecorded statement by LA Weekly art critic Peter Frank17 declaring EZTV was the “first & best place to see computer art displayed publicly in Los Angeles”. 18

Although filmmakers and actors were slow to adopt digital tools, dancers and musicians quickly embraced them. This resulted in the creation of a number of works, including live multimedia, ushering in a world that would become more widely accepted a decade later.

Few commercially available digital art software programs existed, and many digital artists became accomplished computer programmers, writing original code to make their works.

UCLA students Dave Curlender & David Goodsell collaborated on “Larger than Life”,19 a short piece in which they wrote their own computer program. They gained access to a supercomputer at the medical school for rendering and output. It was presented as a work in progress at EZTV in 1984, the only known version of the work known to have survived.

It is important to understand that available computers powerful enough to render high-quality images were extremely rare in the early 1980s. Artists needed to devise individual strategies for creating work in this still-emerging field. And creating animated work was much harder. From gaining limited access to university supercomputers to rigging custom “hot-rodded” home systems out of spare or used parts, each artist had their own approach related to procuring equipment access.

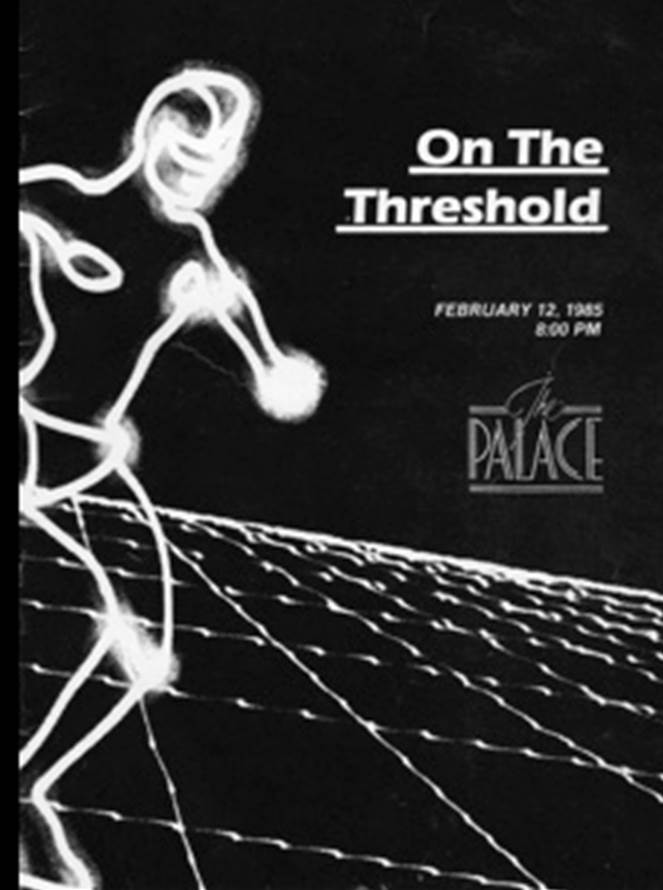

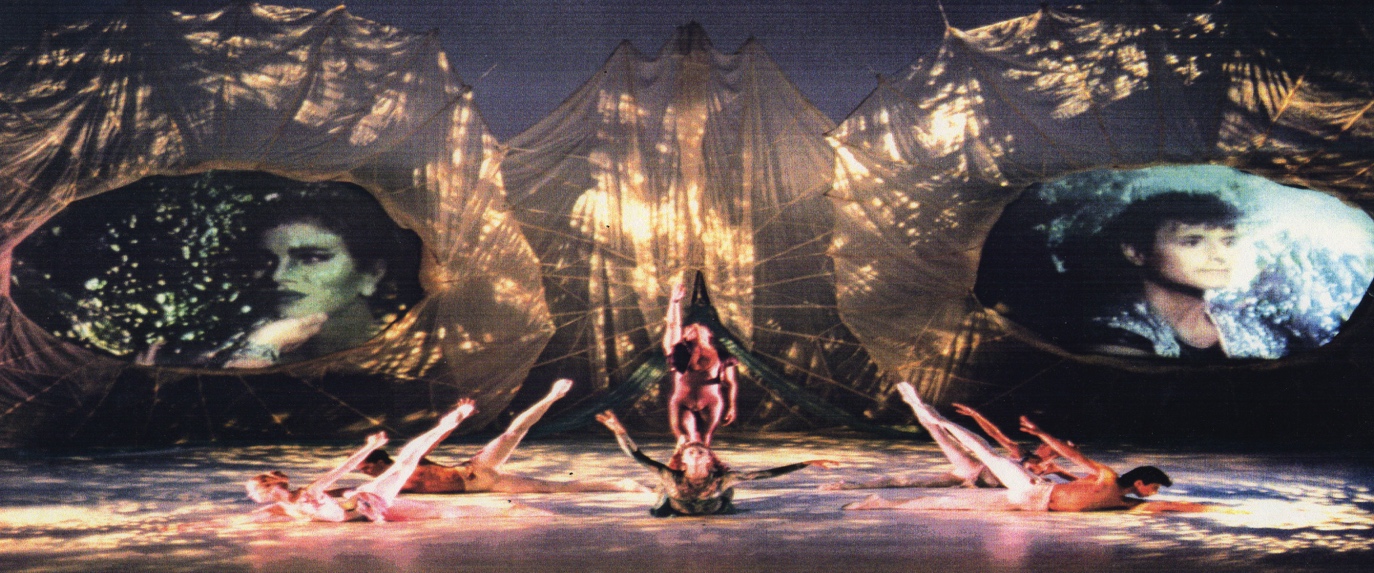

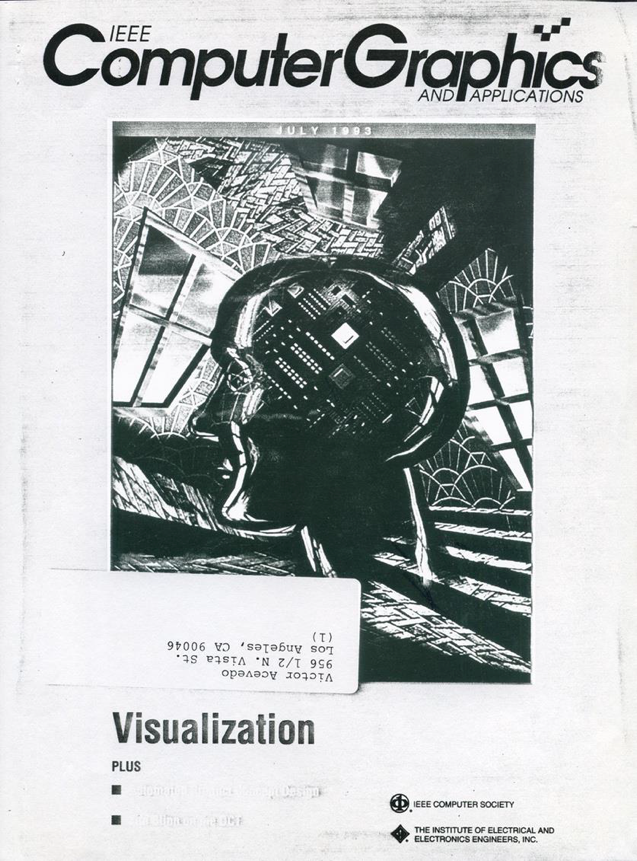

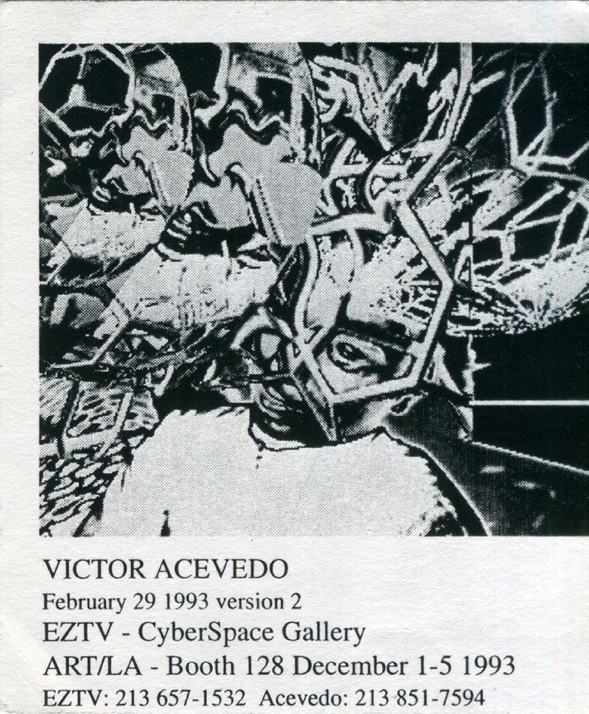

In 1984, producers Joan Collins20 (of LA ACM SIGGRAPH)21 and Robert Gelman, in collaboration with artists such as Ron Hays, assembled a team of artists and technologists to create an evening of live-multimedia performance, integrating dance, music, computing, video projection, lasers, and robotic lighting. They imagined a showcase suggesting where the arts would be heading. The event, “On the Threshold”22 was staged at Los Angeles’s historic theater, The Hollywood Palace, in February 1985. Larger Than Life’s completed version premiered there. Additionally, artist Victor Acevedo,23 an advocate for digital art within the LA art community, curated a wall show of 11 artists, 9 of whom were digital.

Dancers such as Marci Javril collaborated with video engineer/artist Ed Tannenbaum,24 creating a series of live performances involving the live scanning of Javril dancing, processed and projected cinema-sized, using the advanced projection technology of the time, such as the GE Talaria light-value projector.25 I collaborated on three projects with choreographer Eve Lenzer, coder Debbie Winsberg, and writer/performance artist Sandra Tsing Loh,26 creating EZTV’s first theater-sized images. And the beginning of my many live multimedia projects, involving dance, theater or performance art, in the decades to come.

New equipment was also demonstrated. Actor/video artist Radames Pera27 used the Fairlight CVI28 video synthesizer to improvise live abstract projections with several dancers. The CVI was manufactured for a few years but ultimately failed commercially.

On the Threshold was both a laboratory and an exhibition. It anticipated a potential merger between live performance and the digital arts. In some respects, it exemplified the inter-relationship between clubs and the beginnings of gallery and museum acceptance.29

From Video Gallery to Video Center

In 1985, computer artist Joni Carter30 donated to EZTV a Mindset Computer Graphics31 system. This greatly enhanced our digital production capability.

Also in 1985, EZTV moved from a 700 square foot gallery to a three-story facility of approximately 17,000 square feet (with about 7,000 square feet initially useable).

EZTV Video Gallery became EZTV Video Center.

This increase in size provided increased opportunities for larger events, with bigger audiences as well as the creation of five editing rooms, a music lab, a photographic darkroom, a production studio, and offices.

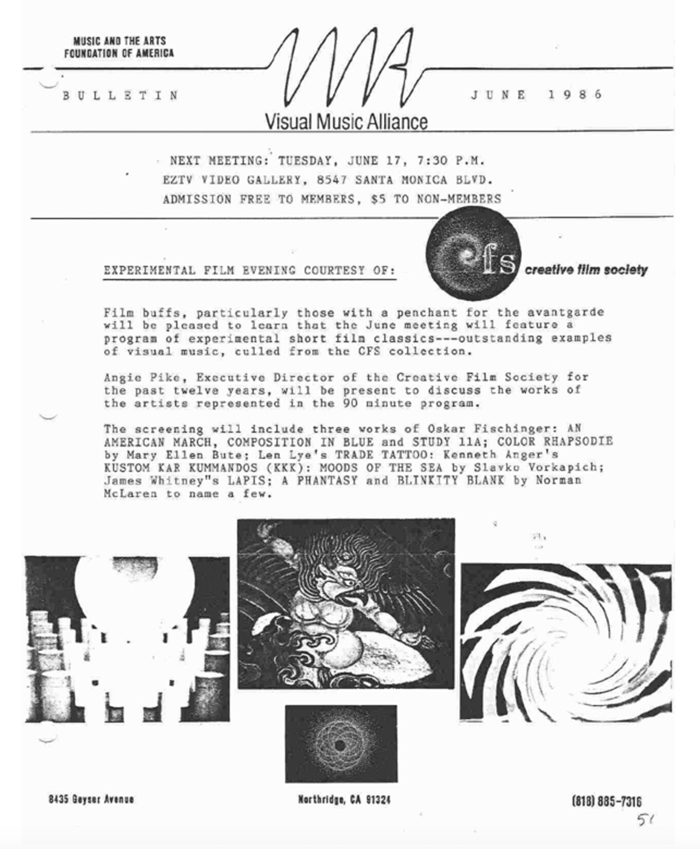

A deliberate expansion into more presentations of digital art began with a series of collaborations with LA SIGGRAPH and exhibitions guest curated by the Visual Music Alliance32 (VMA), and performances by the California Outside Music Association (COMA).

Monthly meetings by VMA brought to EZTV both classic as well as contemporary screenings of visual music, non-narrative, abstract works informed by painting and experimental cinema.

EZTV began presenting classic works in computer art, such as by Ed Emshwiller,33 and John Whitney, Sr.,34 experimental film such as by Chantal Ackerman,35 and visual music films such as by Oscar Fischinger,36 from previous years and sometimes even decades.

Inroads for Women in Digital Art

At a time when artists the Guerrilla Girls, were correctly commenting on the relative lack of presence at galleries and museums by women artists, the computer arts community had a long-standing history of inclusion. This was also in sharp contrast to what was often perceived as the misogynistic tendencies prevalent in 1980s cinema, both mainstream as well as independent/alternative. At this time, few women were being commissioned to be film directors, curators, or artists.

In the sphere of computer art, women often were the auteurs, as directors, curators, and sometimes as the writers of the computer programs necessary to produce their work. Curators and presenters such as Patric Prince,37 Coco Conn,38 Joan Collins, Diane Piepol, artists such as Rebecca Allen,39 Vibeke Sorensen,40 Kim McKillip (aka ia Kamandalu),41 Shelley Lake,42 Georganne Dean, Sherri Rabinowitz,43 and finally Kate Johnson44 altered the public’s perception as to what EZTV was about.

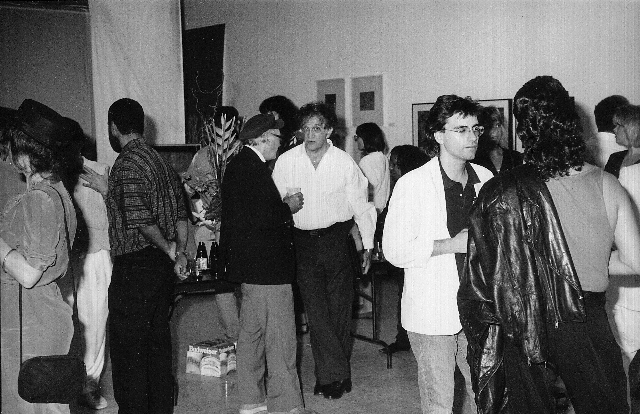

Computer art-related events were among the very best attended at EZTV. This helped to further legitimize the space, expand its audience, and assure its survival. An appetite was being proven that Los Angeles was interested and ready to discover just what artists could do with these newly emerging tools, and how they could benefit their children.

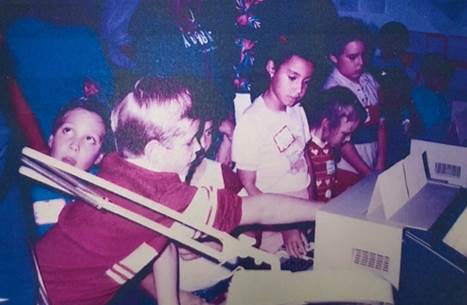

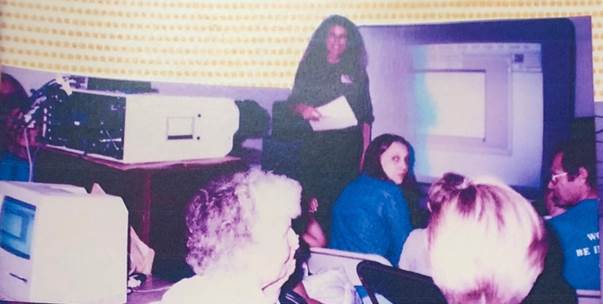

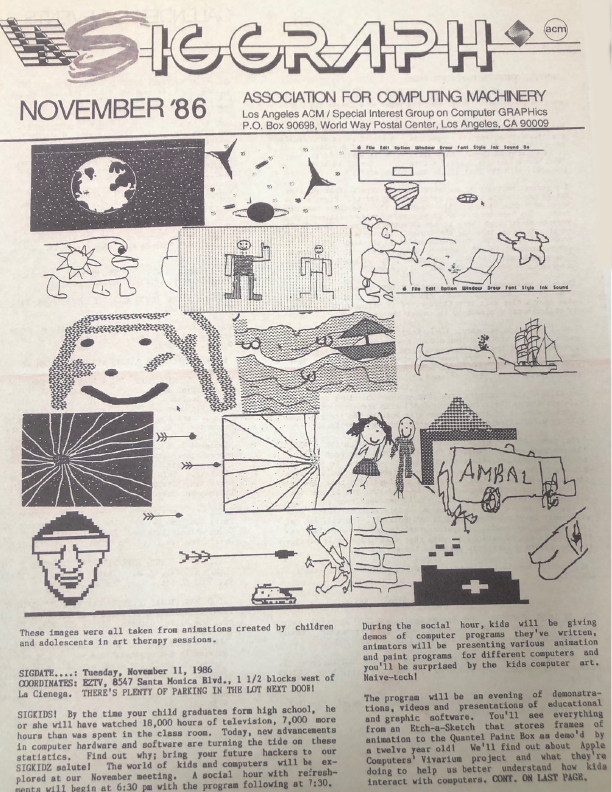

Music video director Coco Conn had become chair of LA SIGGRAPH. In 1986, she staged “SIG KIDS”, an opportunity for children and their parents to experience, often for the first time, what it was to use a computer. There was still controversy among educators as to whether computers should be introduced into classrooms, and Sig Kids helped demonstrate the immense advantages of teaching children to program, create computer art & music, and communicate with each other over geographical distances by using modems to communicate with other students located elsewhere.

Other artists were also adopting digital tools. One of internationally exhibited artist Jim Shaw’s first one-person shows was “The Nuclear Family” (1986), where he combined physical sculptural elements with materials created with the use of computers, demonstrating an early example of the multi-disciplinary nature of computers in arts practices. Mimi Abers’ large-scale sculptures, which also incorporated video monitors displaying computer-based imagery, also pointed to a soon-to-be-reached time when the physical and digital arts would overlap.

I began programming the curation of events to coincide with larger regional events. The first manifestation of this was the newly announced LA Festival,45 with an affiliated festival, Fringe Festival/Los Angeles,46 where I served on the Board of Directors.

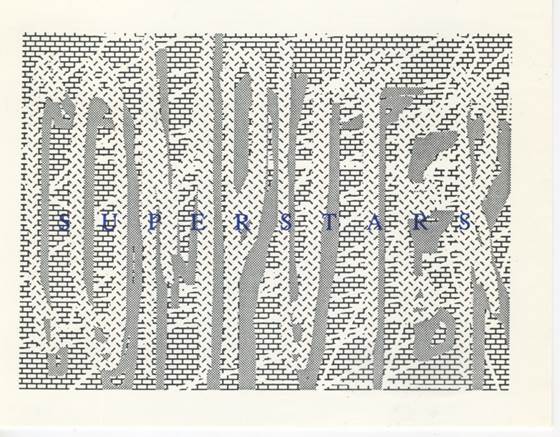

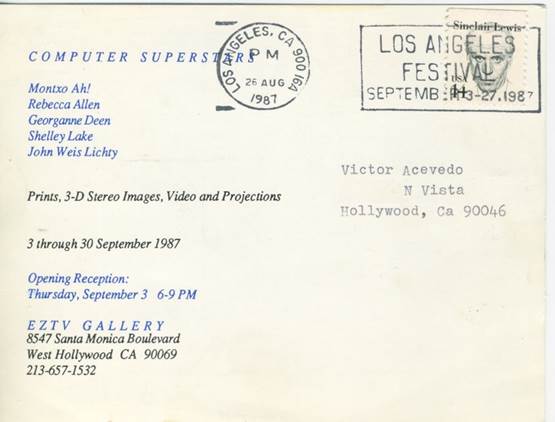

For part of the festival, artist/curator Montxo Ah! (aka Montxo Algora)47 curated “Computer Superstars” that included the first Los Angeles exhibition of Rebecca Allen.

Computer Superstars was the first EZTV group show specifically focused on digital art.

The innovative French“Minitel” (virtually unknown in the USA) was demonstrated during this show, connecting with persons both locally as well as in France. This pointed to the future technologies, such as email, that would become common, almost 10 years later. Dr. Timothy Leary48 loaned an Amiga 200049 to the exhibition and later donated one to me.

Embracing Expanded Cinema

Choreographer Zina Bethune50 (1945-2011) was among the most important figures at EZTV in its first 20 years. As part of EZTV’s 1987 participation in Fringe Festival/LA was “Roadside Attractions” a collaboration between Bethune, Ron Hays, and me. This was a live dance performance accompanied by large-scale projected imagery.

Other EZTV digitally related events included in 1987’s Fringe Festival included:

The year 1988 marked a major advancement in our technical capabilities, resulting in a series of additional collaborations with Bethune that lasted 20. years. Computer-synchronized multi-channel video installations, robotic set and light movement, and experiments with night vision for live performances all began to be produced.

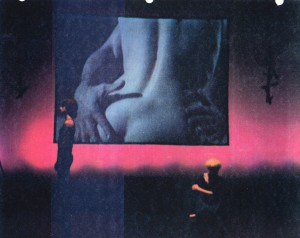

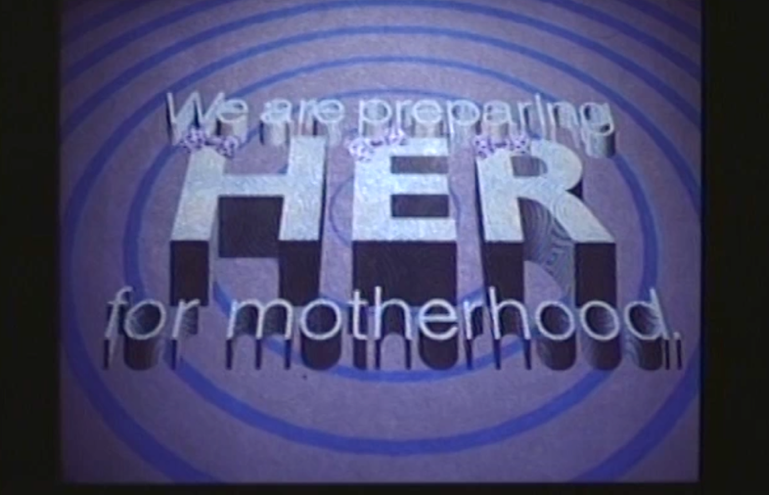

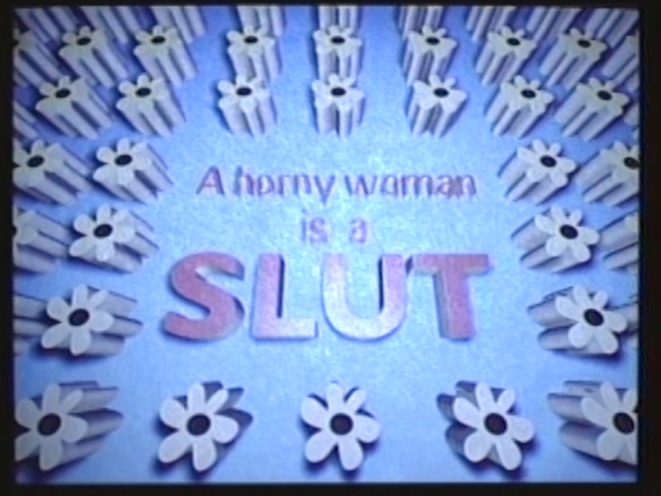

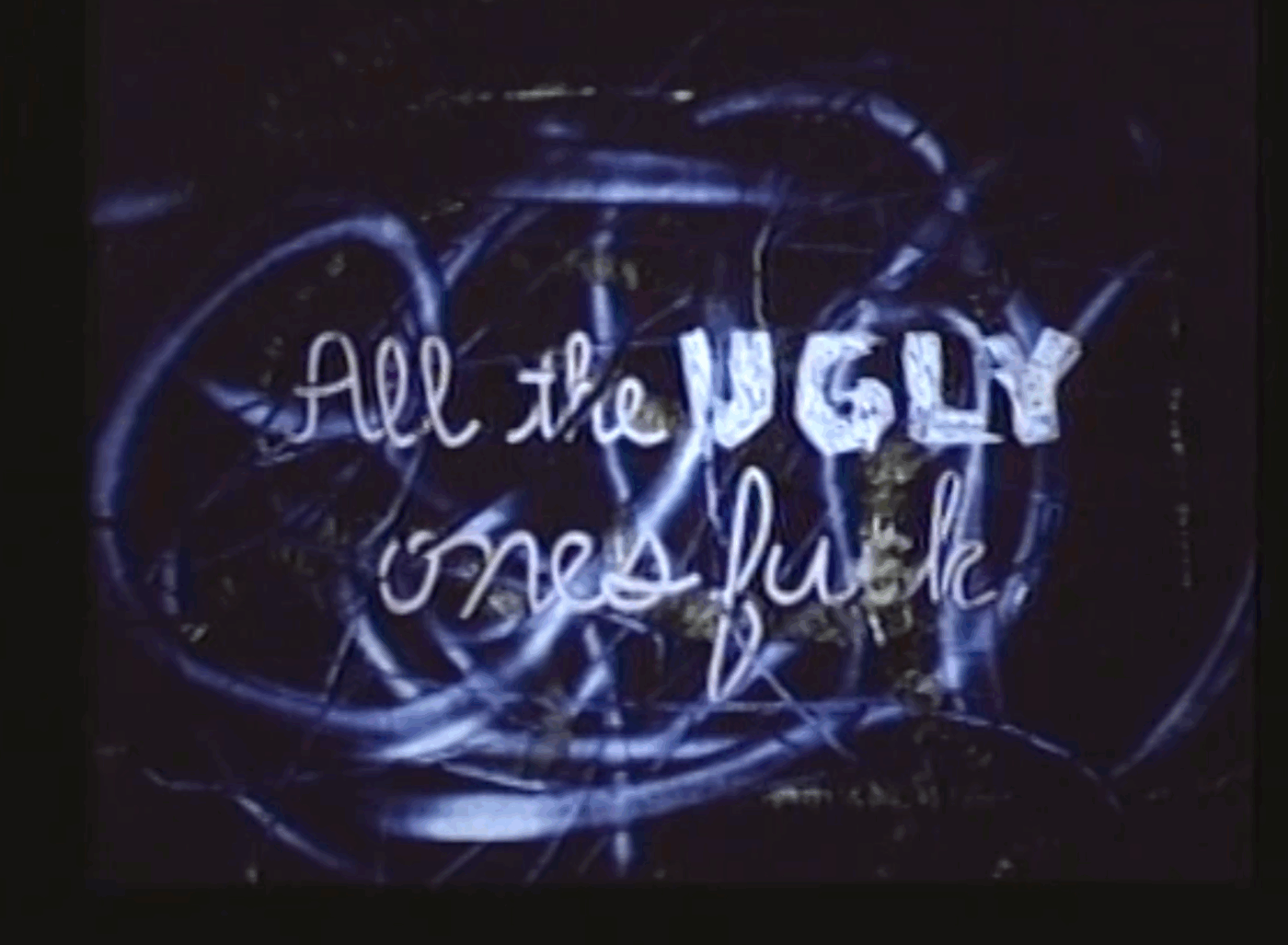

In 1988, I gave media artist Jennifer Steinkamp52 her first one-person show. Reflecting the feminist perspective seen commonly in the contemporary art and performance art genres, Steinkamp’s digital images commented on sexist cliches, bringing further awareness to the liberating role that computers were playing in giving women their voices in society.

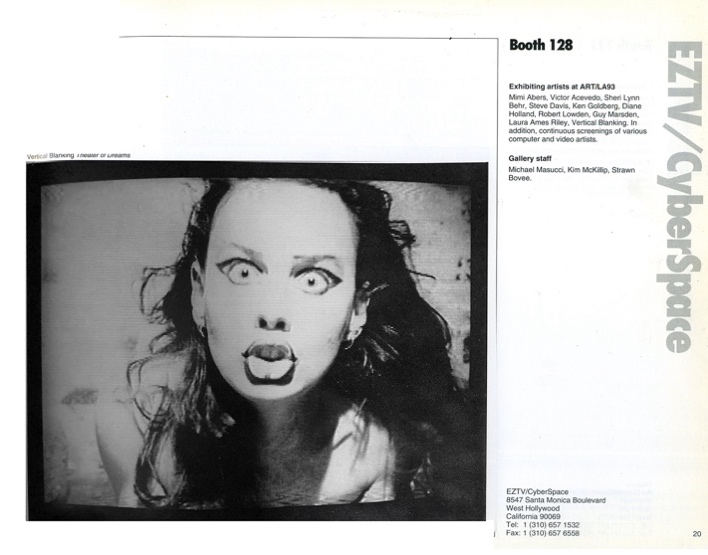

In response to such cliches of female objectification by male artists or directors, many female artists at EZTV choose to empower themselves and, when appropriate to the context of their project, self-objectify. Artists such as Kim McKillip (aka ia Kamandalu), Anneliese Viraldiev, Laura-Lee Coles, and others choose video/digital tools to decide for themselves how and when they would choose their own nudity for their projects.

By 1988, narrative features at EZTV were rare, and digital art was commonplace. There is no way to tell the story of EZTV in the early years without a focus on Kim McKillip. She began working at EZTV in 1986 and immediately took seriously preserving what became the EZTV Archives. She created with me some of the seminal works that allowed EZTV to gravitate more towards greater acceptance within the art world and to EZTV’s survival. Like other women at EZTV, she was comfortable with computers.

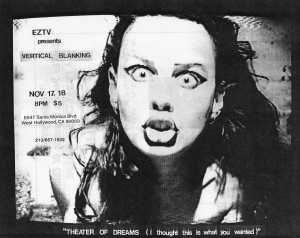

Vertical Blanking & the merger of analog & digital video

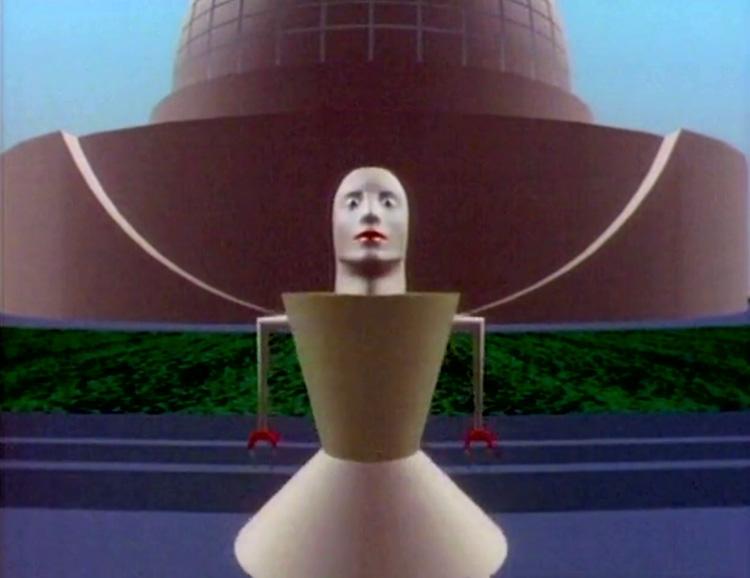

Vertical Blanking (VB)53 was a music/performance/video duo McKillip and I created in 1986, producing a number of videos and live performances. It combined elements of performance art, experimental music, and pop culture iconography. One focus was creating surrealistic work that involved exploration into ufology.54 Other themes included feminism, climate change, surveillance, and consumerism.

VB incorporated techniques more akin to live VJ production into editing rather than conventional post-production, as well as experimental use of self-created sound sampling.

In 1990, EZTV acquired a pre-release model of the Newtek Video Toaster,55 a revolutionary tool that converted an Amiga 2000 into an advanced video production studio. This resulted in an early form of what became known as the analog/digital hybrid: ‘desktop video.’ These hybrid video productions began to use personal computers as part of the direct post-production chain, allowing for effects and graphics previously only attainable through expensive technologies such as Ampex Digital Optics.56 Vertical Blanking was among the first artists creating these new hybrid works to be reviewed by mainstream film critics.57

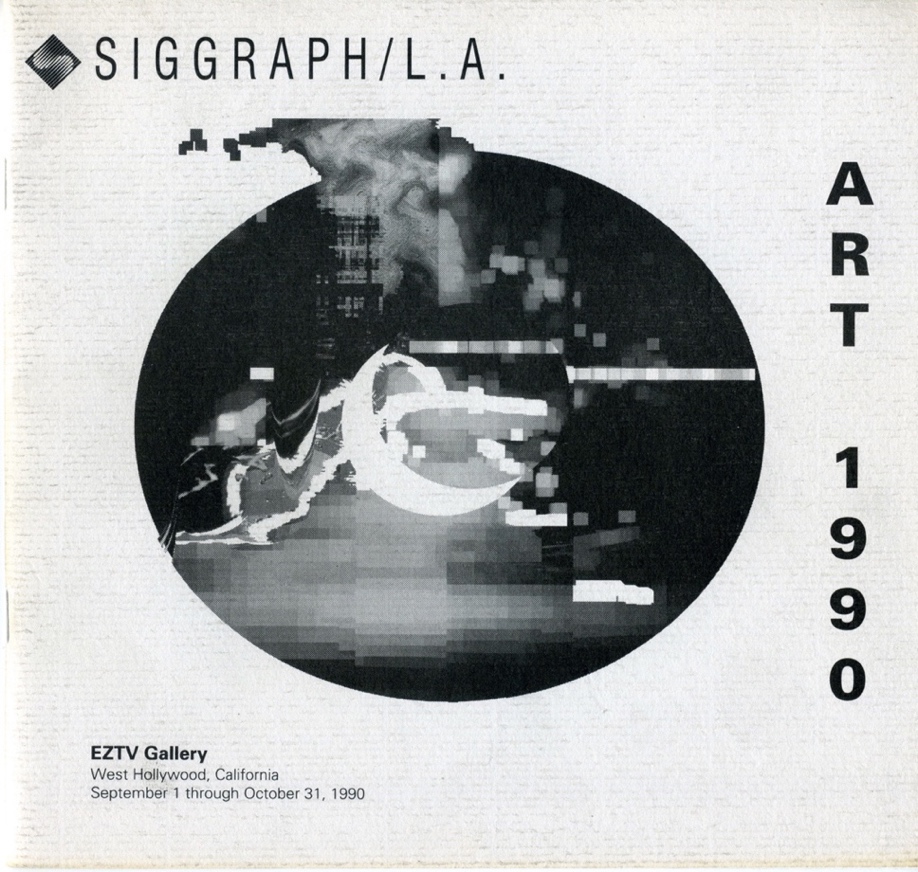

In 1989, Victor Acevedo introduced me to historian/curator Patric Prince. They proposed a museum-level group show of digital artists, including early adopters such as David Em.58

I programmed it to coincide with Fringe Fest ’90. Prince curated “ART 1990”59 a group exhibition of leading computer artists: Victor Acevedo, Rebecca Allen, Max Almy & Teri Yarbrow, Gloria Brown-Simmons, Ronald Davis, David Em, Shelley Lake, Tony Longson, Stewart McSherry, Kamran Moojedi, Karl Sims, Vibeke Sorensen & James Wrinkle. This exhibition received media coverage, including in actor/art collector Vincent Price’s television program on arts & culture,60 as well as a local television program on the arts.61

The Cyberarts International Conferences62 were a three-year series produced by Keyboard Magazine,63 Publisher/Editor Dominic Milano,64 and Robert Gelman. It was part of the Fringe Fest ’90. It included contributions for all three years by Vertical Blanking, including an early use of night vision technology for live performance. Performances also included Todd Machover,65 using his “MIDI Glove,”66 to conduct live musicians.

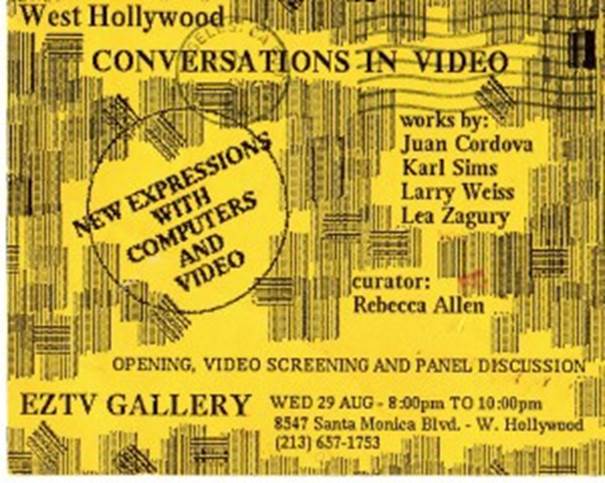

1990 also saw additional digital art exhibitions, such as a solo exhibition by Mason Lyte, as well as a group exhibition and panel discussion curated by Rebecca Allen.

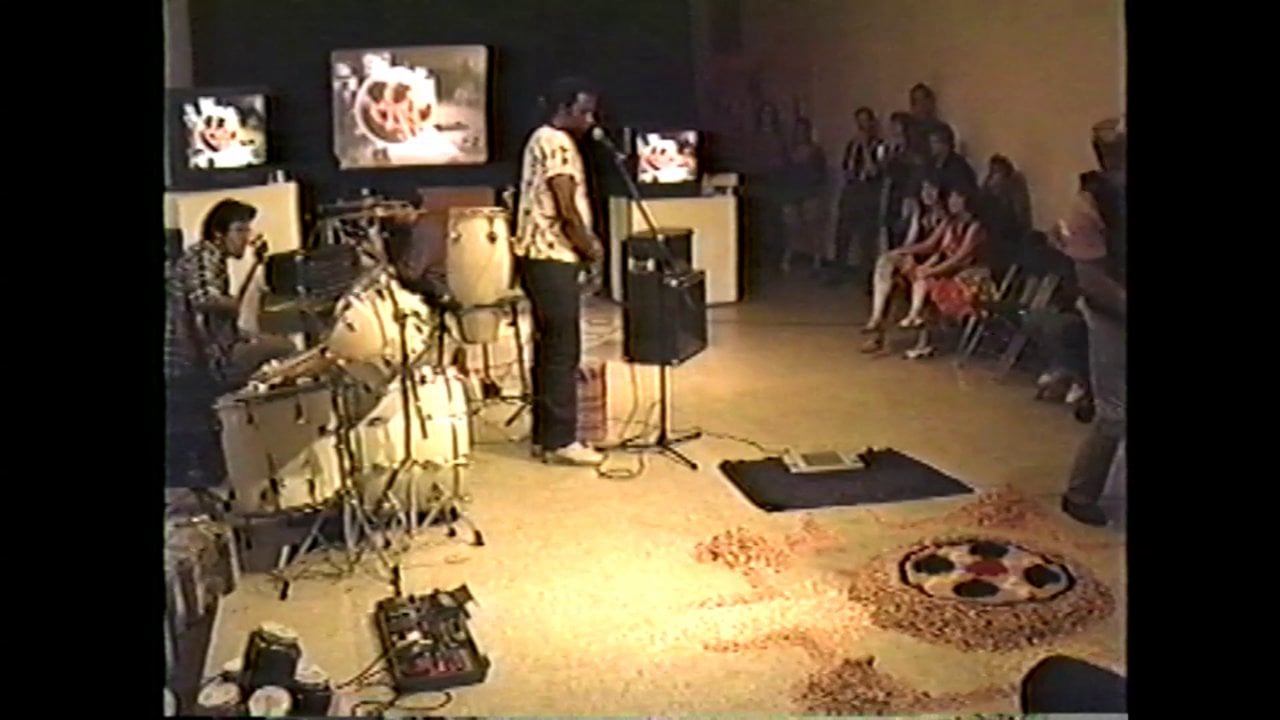

In collaboration with Electronic Café International,67 several experiments in telepresence took place. These included a transmission from NYC to West Hollywood with Clyde Casey (1950-2021),68 dance experiments with Mark Coniglio & Dawn Stoppiello (Troika Ranch),69 and performance artist/musician Ulysses Jenkins.70

The most technologically advanced live multimedia performances at EZTV during its West Hollywood years, featured several performances in 1990 by a music/video/digital group called InTone.71 InTone combined live music, interactive computer programming, with a number of channels of digital, still photographic, and video imagery, both projected on several screens as well as on numerous video monitors.

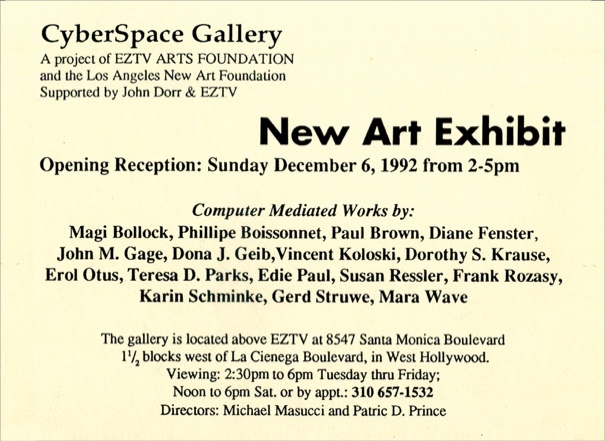

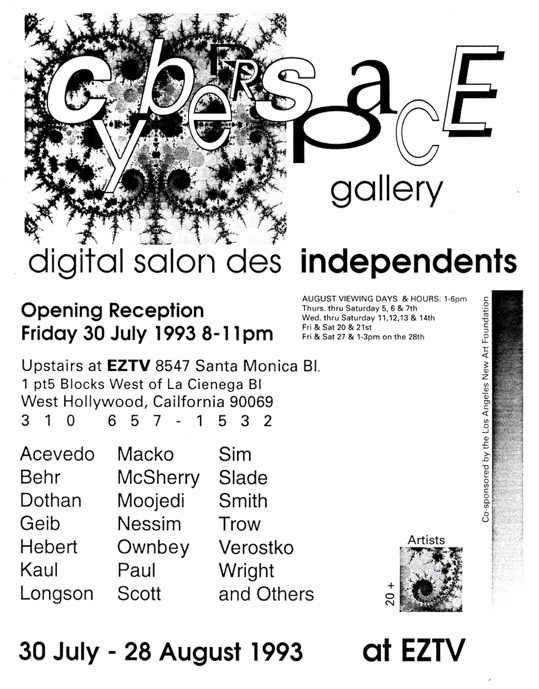

The year prior to John Dorr’s death required an honest appraisal of what had worked and what had not during the years since 1979. After almost a decade of curating digital art, a decision was made to radically alter EZTV Video Center. Together with Patric Prince, and with the help of Victor Acevedo, Kim McKillip, Michael Wright, Lisa Tripp, and LA SIGGRAPH, I created an early space dedicated to digital art. John Dorr, recognizing the narrative video days of EZTV were behind us, offered to give the production studio over to us, to convert it into CyberSpace Gallery. According to a year-long exhibition in 2023 on Patric Prince, at the Victoria & Albert Museum, CyberSpace Gallery “literally put digital art on the map.”72

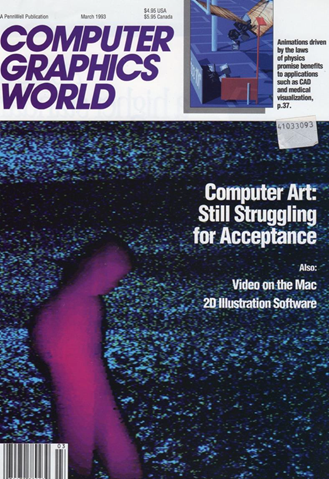

CyberSpace Gallery received attention in both the popular press as well as in publications dedicated to computer graphics as well as engineering, greatly expanding the reputation of digital art, the artists, as well as EZTV.

In addition to these several solo and group shows, live performances and panel discussions were presented. Dr. Timothy Leary presented a series of live multimedia events,73 including live multimedia performances by P-Orridge,74 Dr. Fiorella Terenzi,75 which can be seen in EZTV’s 1996 documentary on Leary,76 created for the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, where it premiered. It is likely Leary’s last video interview. The interview is conducted by Transhumanist thinker,77Dr. Natasha Vita-More.78

For the finale of the three years of the CyberArts Conferences, on Oct. 31,1992, SONY loaned Vertical Blanking, in collaboration with Zina Bethune, two experimental Betacam cameras,79 specially equipped with night-vision capability. These were originally designed for military use. SONY also loaned 2 state-of-the-art projectors, scaffolding, and the air-cooling system required to operate them. Along with robotic sets, computerized video hardware, a live dance company, and live & pre-recorded actors, VB premiered “Pain or Gain” (aka “Pain Game”), which spoofed the impending adoption of VR technology.

Vertical Blanking’s last live performance was in Dec.‘92, for the finale of the Los Angeles Macintosh Users Group massive holiday party. Timothy Leary was the MC. What is funny about that, is we were not using Apple computers. We were still using Amigas. The organizers of the event told us to ‘simply not say how we were doing what we were doing, and the audience will assume it was done with Macs.’

A few weeks later, John Dorr died on January 1, 1993. Vertical Blanking was at the height of its popularity, with the support from SONY and the potential for wide commercial success.

Three days later, Dr. Timothy Leary invited McKillip & me to his home. He took out his best whiskey, and we sat down to discuss the future. Leary said he believed that we would not abandon EZTV and would leave behind our opportunities for Vertical Blanking to focus on saving EZTV.

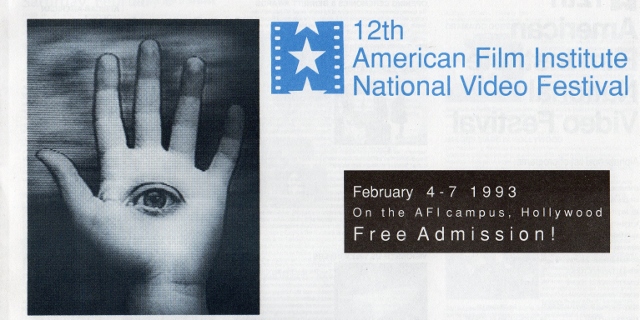

A month later, the American Film Institute’s annual National Video Festival was named that year in honor of John Dorr and his efforts at EZTV.

Leary correctly predicted I would stay with EZTV and find a way to help it survive. Somehow, with the help of Kim McKillip and a handful of dedicated and tireless team members, we did. And at the time of this writing, in July, 2025, somehow, we still are here.

EZTV West Hollywood’s last chapter

A number of digital art-related projects had been in planning for, in some cases, a year before. These were carried out right up through the end of EZTV’s tenure in West Hollywood, in January 1994. These included “Pictures from the Hyperworld,” an exhibition and panel discussion produced by Peter Lunenfeld, programmed to coincide with SIGGRAPH’s seminal exhibition “Machine Culture”,81 curated by Simon Penny.82

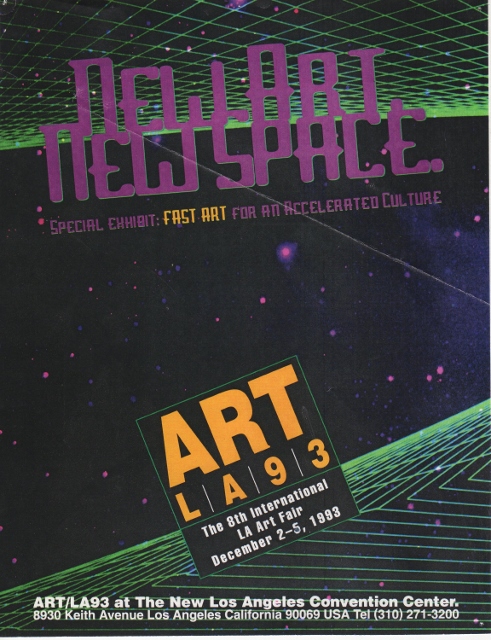

Towards the end of 1993, ART LA 93,83 was booked for the grand re-opening of the greatly expanded LA Convention Center.84 The center grew from one block to three.

I was commissioned, along with KCRW85 DJ Liza Richardson86 to curate “Fast Art for an Accelerated Culture,” a series of EZTV-related digital events. In addition to Vertical Blanking, nine other artists were presented. Ken Goldberg87 exhibited a telepresence piece, where attendees could place their arm into a steel tube that transmitted haptic information to MIT Media Lab, where people could virtually ‘touch’ the arm of the attendee at our booth.

EZTV’s chapter in West Hollywood concludes with the introduction of Kate Johnson88 (1969-2020). She arrived in the summer of 1993 to help finish John Dorr’s last work (in collaboration with Mike Kaplan),89 a documentary on Robert Altman, “Luck, Trust & Ketchup.” Without her, it would have never been completed.

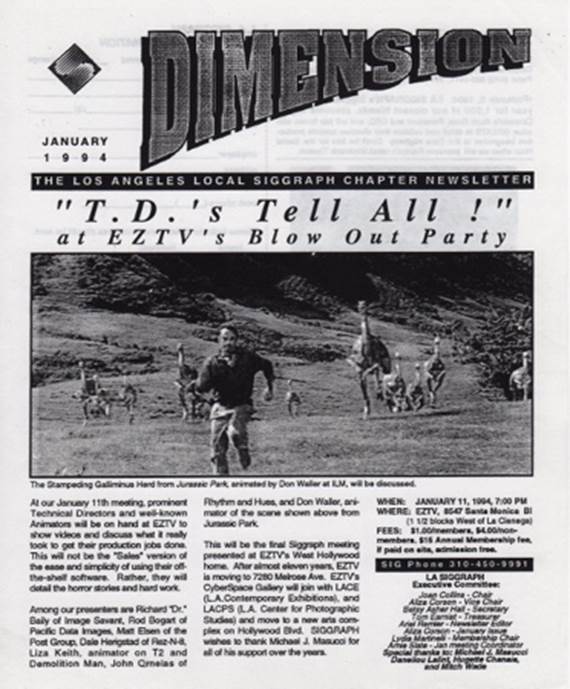

On January 11, 1994, the final event to take place at EZTV Video Center was hosted by LA SIGGRAPH. Joan Collins, who had begun working with EZTV a decade before, was now Chair. The celebratory evening was both a formal lecture/presentation by leading Hollywood Digital Effects professionals, as well as a party, closing the center, and ending EZTV’s West Hollywood years.

This overlapping of communities, sharing a common interest in the transformative developments, inventions, and applications that seemed to evolve each year, continues to this day and helped solidify what EZTV was to become in the post-1993 years.90 By the end of EZTV Video Center’s existence in West Hollywood, digital art had become the dominant and most recognized aspect of the space. As stated in Venice Magazine, we had by then been “programming computer-based exhibitions at EZTV for almost ten years.”91

Preserving and expanding on the legacy of EZTV’s West Hollywood years.

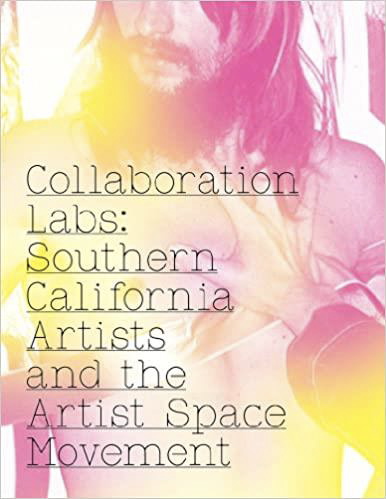

The process of historification for EZTV has been long and difficult. And has still only just begun. When Kate Johnson arrived in mid-1993, the death of John Dorr had left the organization in financial ruin and an existential crisis. She helped save it, preserved its early archives, and advocated for its history. Without her, EZTV would likely have faded in memory, soon to be forgotten. And this website would never exist. She was indispensable in working with curator Alex Donis,92 in preparation for his inclusion of EZTV in the 2011 Getty Pacific Standard Time Los Angeles Art: 1945-80(PST).93 In addition to a focus on EZTV’s early narrative works, Donis included “Standing Waves”, as well as Curlender/Goodsell’s “Larger Than Life”, and a reprise of Emshwiller’s “Sunstone” in his PST exhibition: COLLABORATION LABS: Southern California Artists and the Artists Space Movement.94

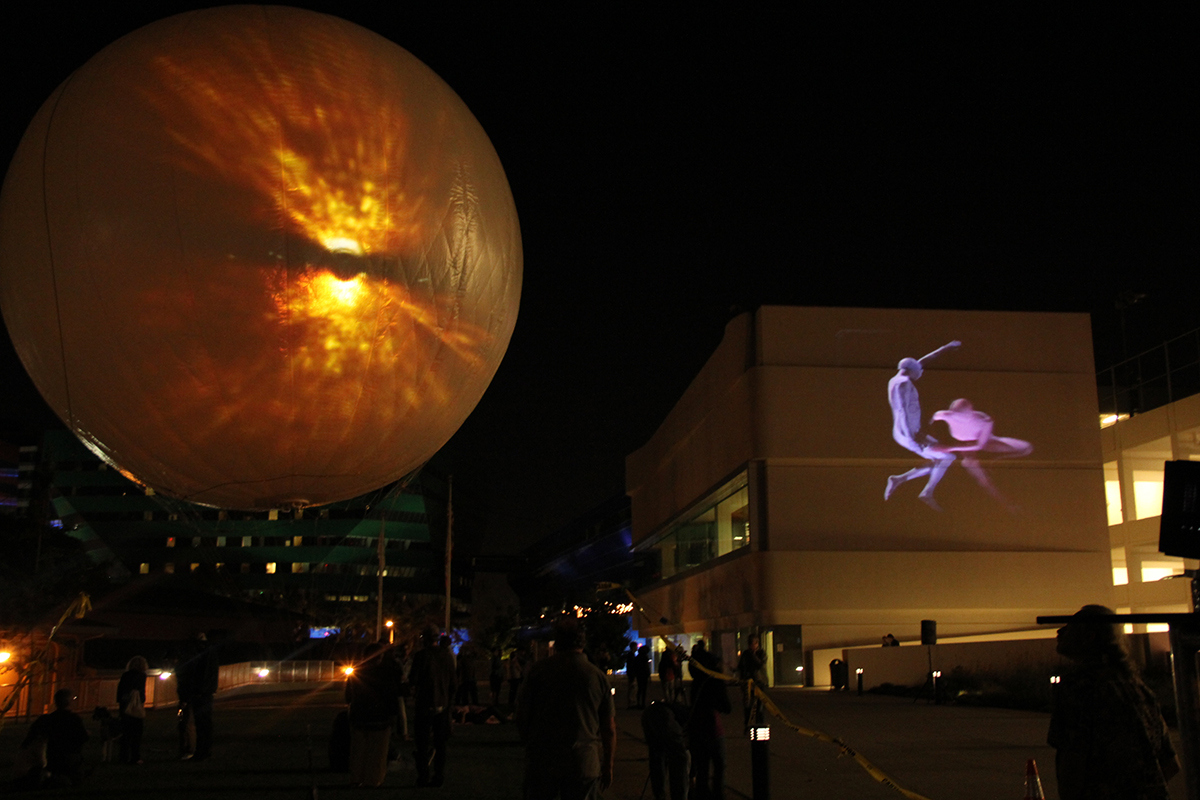

Coincidentally, Kate Johnson was commissioned to create digital projections for the Getty PST’s gala opening. She concluded the campus-wide projection-mapping experience with EZTV’s PST-included videos, projected on a massive scale onto all the buildings of the Getty. The EZTV logo was part of the concluding images.

Inclusion in the Getty’s PST in 2011 led directly to 2014, when, for the 35th anniversary of EZTV, curator David Frantz,95 acquired some of EZTV’s early archives for USC’s ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives.96 A three-month series of exhibitions, screenings & panels followed, including a screening in NYC at Anthology Film Archives.97

The 2011 Getty PST, and 2014 USC ONE Archives events paved the way for a new and expanded recognition of the complex history of EZTV.

In 2015, I was asked to speak at the College Arts Association’s national art history conference on EZTV’s digital art history.98

In 2019, researchers Sibylle de Laurens & Pascaline Morincôme presented four events about EZTV99 in collaboration with the Kandinsky Library, Centre Pompidou. Those were followed by an exhibition of ephemera in the library, of EZTV materials, including some materials related to many of the events discussed here.

In 2024, for EZTV’s 45th anniversary, an exhibition presenting 40 years of collaborations between EZTV and LA SIGGRAPH was staged at Barrett Gallery, Santa Monica College100. And, DNA Festival Santa Monica101 was formed. “Hacking the Timeline”,102 presented in collaboration with Robert Berman Gallery,103 was a panel discussion104 about digital art history. Panelists were Dr. Pietro Rigolo (Getty Research Institute), Joel Ferrere (LACMA), Melanie Lenz (Victoria & Albert Museum), and Pascaline Morincôme.

The panel was listed among the best of the over 70 events included in the 2024 Getty PST.105

Vertical Blanking received its first retrospective106 in 2025 at REDCAT, curated by Elizabeth Purcell & Alex Gootter as part of their 11-event, 9-day, 7-venue series107 on early EZTV.108

From its earliest days presenting work on small TV monitors and early nightclub projectors, to producing some of the largest images to date in Los Angeles, EZTV transformed from a gallery & early microcinema to megacinema, multimedia producer, and online museum.

There are other histories related to the complex and sometimes seemingly contradictory story of EZTV. Besides narrative fiction and digital art, other concurrent histories are also related to documentaries, performance art, and paintings. Together they form the full story.

Special thanks to Victor Acevedo for archival photographs and ephemera.

https://museumoffailure.com/exhibition/sony-betamax

2

https://www.myoldcomputers.com/museum/computers/atari_800.htm

3

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/tXXD9dPPIx0

4

https://www.oxfordduplicationcentre.com/History-of-U-Matic-Tapes.html

5

https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=Atari%20BASIC

6

7

https://www.siggraph.org

8

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-04-19-mn-21-story.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/04/23/obituaries/ron-hays-multi-media-artist-45.html

9

https://www.computinghistory.org.uk/det/3959/Atari-800XL/

10

https://atarimuseum.ctrl-alt-rees.com/computers/8bits/xl/xlperipherals/1030.html

11

https://subnetzero.info/2019/08/15/before-the-internet-the-bulletin-board-system/

12

http://www.videogameconsolelibrary.com/pg80-rdi.htm#page=reviews

13

https://psap.library.illinois.edu/collection-id-guide/opticalmedia

14

https://www.afi.com

15

https://lasiggraph.org/bio/presenter/beeton-maija

16

17

https://curatorsintl.org/about/collaborators/5809-peter-frank

18

19

https://eztvmuseum.com/heztv-wh-larger-than-life

20

https://lasiggraph.org/sites/default/files/lash/1985/nl/1985_02_threshold.pdf

21

https://lasiggraph.org

22

https://lasiggraph.org/sites/default/files/lash/1985/nl/1985_02_threshold.pdf

23

https://www.acevedomedia.com

24

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=98fvPSNpw

25

https://streamout.net.au/video-projection-history-the-talaria/

26

https://lohdownonscience.com/about-us/

27

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0672673/

28

https://fairlightcvi.com/?page_id=2

29

30

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/07/14/style/style-makers-joni-carter-computer-artist.html

31

https://bytecellar.com/2004/04/02/mindset_compute/

32

https://www.centerforvisualmusic.org/CVMVMA.htm

33

https://film-makerscoop.com/filmmakers/ed-emshwiller

34

https://www.awn.com/mag/issue2.5/2.5pages/2.5moritzwhitney.html

35

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0001901/

36

https://mymodernmet.com/oskar-fischinger/

37

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/patric-d-prince-digital-art-visionary?srsltid=AfmBOooPR5Jpf2AGPzbyhI94wN0G65mqoRBf-gflKBeuVw7O-zPAUTbt

38

https://lasiggraph.org/bio/presenter/conn-coco

39

https://www.rebeccaallen.com/about

40

http://vibeke.info/about/

41

https://filmmakermagazine.com/tag/ia-kamandalu/

42

https://shelleylake.com/about

43

https://digitalartarchive.at/database/artist/325/

44

https://digitalartarchive.at/database/artist/325/

45

https://www.nytimes.com/1987/08/15/arts/a-festival-of-arts-in-los-angeles.html

46

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-09-04-ca-3865-story.html

47

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm4624306/

48

https://psychology.fas.harvard.edu/people/timothy-leary

49

http://amiga.resource.cx/mod/a2000.html

50

https://eztvmuseum.com/force-of-nature-the-life-of-zina-bethune/

51

http://www.hour25online.com

52

https://dma.ucla.edu/people/jennifer-steinkamp

53

https://www.screenslate.com/articles/screen-memories-conversation-michael-j-masucci-vertical-blanking-and-eztv

54

https://www.screenslate.com/articles/watch-skies

55

https://amiga.resource.cx/exp/p=videotoaster

56

https://www.storagenewsletter.com/2023/09/12/culture-of-innovation-and-technical-achievement-at-ampex/

57

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-09-16-ca-767-story.html

58

https://www.davidem.com

59

60

61

https://youtu.be/953KUN_p-Zw and https://youtu.be/JYt2FVrBKE4

62

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CyberArts_International

63

https://www.facebook.com/KeyboardMagazine/

64

https://ww1.namm.org/library/oral-history/dominic-milano

65

https://eztvmuseum.com/heztv-wh-todd-machover-and-ensemble-at-cyberarts

66

https://hackaday.com/2010/05/12/midi-gloves/

67

https://www.ecafe.com/index.html

68

https://www.vianolavie.org/2012/05/11/clyde-casey-a-new-orleans-mobile-percussionist-47944/

69

https://dawnstoppiello.com/creating/troika-ranch/

70

71

72

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/patric-d-prince-digital-art-

73

“Everything You Know is Wrong”, LA Weekly Dec, 11, 1992

74

https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-51893184

75

https://case.fiu.edu/about/directory/profiles/terenzi-fiorella.html

76

77

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/transhumanism

78

https://www.natashavita-more.com

79

https://www.redsharknews.com/production/item/5454-betacam-changed-the-video-world

80

https://jackiekain.com/afi-national-video-festival/

81

https://digitalartarchive.siggraph.org/exhibition/siggraph-1993-machine-culture/

82

https://art.arts.uci.edu/simon-penny

83

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-12-01-ca-62785-story.html

84

https://www.laconventioncenter.com

85

http://kcrw.com

86

https://www.lizarichardson.biz

87

https://whitney.org/artists/9727

88

https://artillerymag.com/kate-johnson-1969-2020/

89

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0438332/

90

https://digitalartarchive.at/database/institution/608/

91

“Byte Me! Computer Art at EZTV”, Venice Magazine, Aug 1993

92

https://www.alexdonis.com

93

https://www.ocregister.com/2010/01/27/getty-foundation-gives-31-million-to-26-socal-arts-institutions/

94

https://18thstreet.org/collaboration-labs/

95

https://curatorsintl.org/about/collaborators/7492-david-evans-frantz

96

https://one.usc.edu/taxonomy/term/81

97

https://one.usc.edu/program/one-dirty-looks-nyc-present-eztv-anthology-film-archives

98

99

100

https://artnowla.com/2024/07/19/dna-digital-art-festival/

101

https://www.dnafestivalsm.com

102

https://pst.art/en/events/panel-discussion-hacking-the-timeline

103

http://www.robertbermangallery.com

104

https://www.thecorsaironline.com/corsair/2024/9/28/hacking-the-timeline-integrating-digital-art-into-mainstream-art-history

105

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/pst-best-shows-innovation-redcat-1234721317/

106

https://www.redcat.org/events/2025/vertical-blanking

107

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/movies/newsletter/2025-03-21/eztv-video-blonde-death-vertical-blanking-noir-city-bong-joon-ho-the-thing-incredibles-iron-giant-kundun-cook-thief-wife-lover-indie-focus

108

https://filmmakermagazine.com/130958-profile-joanne-mcneil-eztv/