« Out to See Video »: EZTV’s Queer Microcinema in West Hollywood [anglais]

Julia Bryan-Wilson, 2014

“We do not go out to see video,” wrote Douglas Davis in his 1977 account of the distinction between “filmgoing” and “videogoing.”1. According to Davis, the difference between film and video pivots on their divergent methods of circulation and reception. Spectators consume film as a collective “formal occasion” to be witnessed start-to-finish outside the home, while video offers a quasi-televisual “private occasion” that does not require a special cinematic environment.2 Though Davis’s false binary was being dismantled even as he was writing, venues for screening narrative, event-based video were in fact few in the late 1970s, and opportunities to “go out to see video” were hence scant.

This article takes up the unintentional double entendre in Davis’s formulation, tracing the institutional history of an “out” queer space—EZTV, the earliest known video theater in the United States—that was founded in West Hollywood to host communal evenings of viewing that were akin to watching independent film and were meant to resist the more distracted, isolated brand of video-going pervasive in museums and galleries 3. I situate this video theater within a shifting landscape of greater Los Angeles, extending David E. James’s statement that “avant-garde cinemas take place” by considering the importance of location for EZTV’s do-it-yourself video productions and screenings. As James continues, “Existing geographically as well as historically, they emerge from, occupy, and articulate specific spatialities. »4 In the case of EZTV, this “specific spatiality” was not only geographic but social —an “out” gathering space that included sharing skills, creating alternative representational practices, building communities, and fostering desire.

Along with the local roots of “expanded cinema” (first circu- lated by Gene Youngblood in a series of articles in the Los Angeles Free Press), Los Angeles also has a long history of queer underground film, from Kenneth Anger’s influential work to the surge of gay male porn theaters in the 1970s 5.EZTV emerged within these multiple milieus, but it took a divergent path, as it promoted independent video more or less regardless of its content, consolidated production and reception in one location, and welcomed amateurs and professionals alike. EZTV also never explicitly labeled itself gay or queer, which is likely why the microcinema (later a crucial site for HIV/AIDS activism in Southern California) is not well-known with in accounts of queer video 6. Recounting the history of EZTV is not undertaken merely to add a new chapter to the story of expanded cinematic/alternative video practices but to suggest that this kind of collectively viewed video meant to operate as a queer mechanism of incorporation, forming and re-forming tentative and temporary publics, an incorporation that was in an oblique dialogue with the literal incorporation of West Hollywood and its consolidation and marketing as a gay-male “creative” city in the 1980s.

KGAY: Closed Circuit from West Hollywood

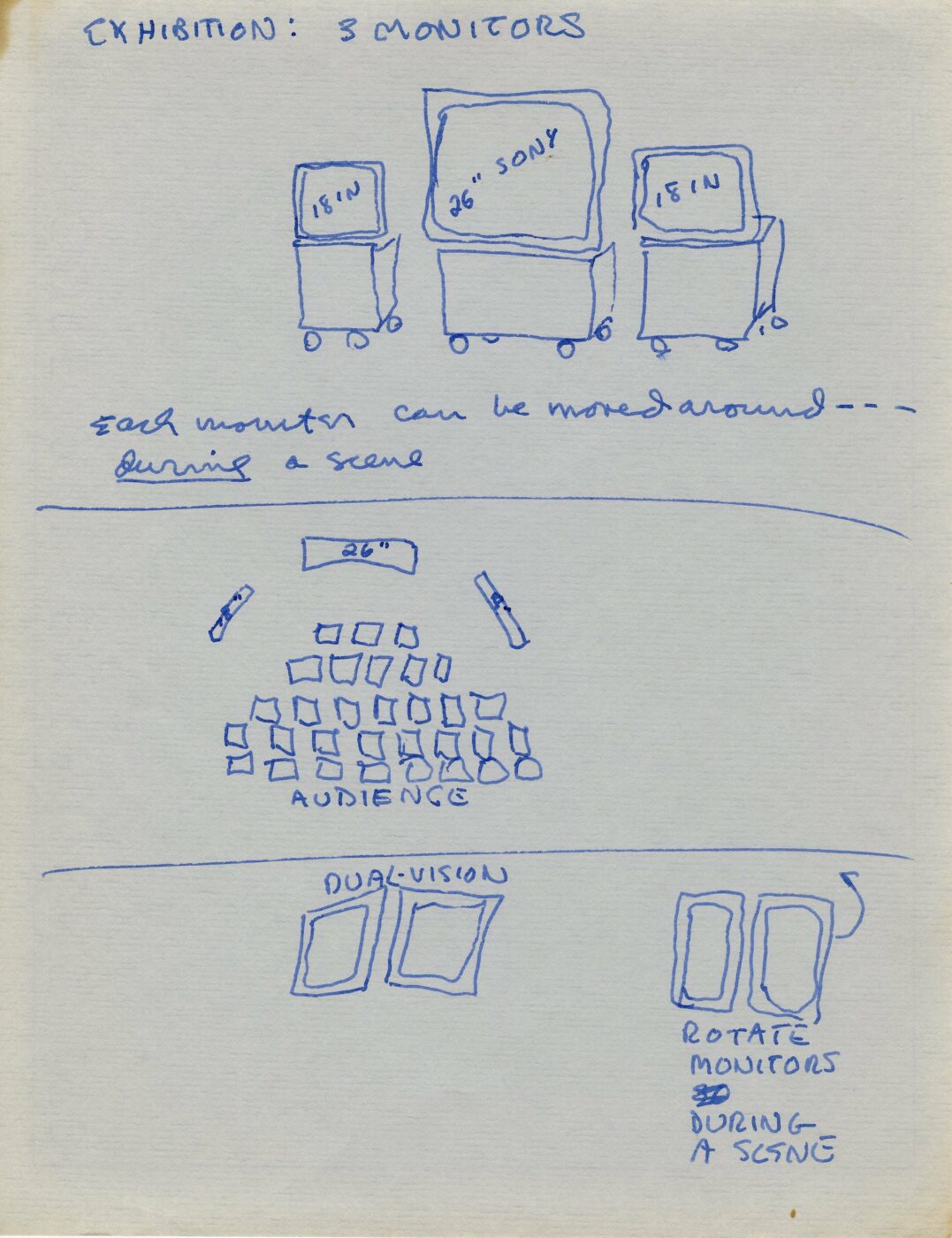

In 1978, queer artist and screenwriter John Dorr had an idea: to inaugurate a facility in West Hollywood dedicated to showing local, independent video—a space that would become a pioneering microcinema, one of the first of its kind (gay or straight). 7 He envisioned this site as “a production and marketing corps for independent video makers,” as well as a screening room that would facilitate public viewings. 8 The screening room, however, was not typical for the feature-length works he envisioned showing. Preliminary sketches from Dorr’s notebooks detail his first thoughts about how such a site might operate, given that portable video projection technologies were not yet commercially available —the tapes would be shown on small, bulky television monitors. Artists such as Peter Campus had been using cathode-ray tube projections in video installations in the early 1970s, but such equipment hit the market for a wider audience only in 1982 9. In a drawing from his notebooks, Dorr outlines three separate arrangements of screens and spectators in a plan that accommodates diverse monitor sizes as well as expands to include variable audiences.

At the top, Dorr envisions monitors on wheels that can be moved around during the screening to provide a novel, flexible understanding of how feature-length videos could be viewed, moving them away from flickering images contained inside static furniture and instead utilizing the monitors themselves as roving agents that are activated during specific scenes. This malleability of screening systems was considered one innovative effect of video’s adaptable technological apparatuses in the wake of Youngblood’s notion of “expanded cinema”. 10 On the bottom of this page, a proposal for a dual-monitor viewing system suggests that Dorr understood that the screens might rotate or shift in relationship not only to each other, but also to the pictures they displayed. Though projection in both film and video had been experimented with for over a decade as a way to reshape the screen/image/audience encounter —including such iconic examples as Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie-Drome (1963–1965) or Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966–1967)—what Dorr proposed differs from these examples. Rather than phenomenological explorations or immersive environments that challenged linear filmic conventions, Dorr wanted to show narrative feature videos meant be viewed in their entirety. 11

Dorr’s proposed mobile configuration was, in 1978, a somewhat unconventional spatial proposal for viewing video. Museums that screened videos usually invited spectators to sit on benches in the middle of a gallery space or, more frequently, to stand while watching and leave when their attention waned. 12 Video was not commonly treated as a mobile unit or surrogate performer that could be shuffled around or choreographed during different points in the image flow; rather, it acted as a fixed sculpture carefully emplaced in relationship to other visual elements. Within a gallery context, the monitor’s rectilinear face suggested its continuity with wall-based work—one more frame among others. Even when placed on a cart with casters, the equipment was usually tethered in place by its nest of cords, not steered around. By contrast, “each monitor can be moved around— during a scene,” wrote Dorr on the drawing, and “rotate monitors during a scene,” emphasizing that the screens would be set in motion rather than remain a bank of frozen hardware.

Present in Dorr’s sketch is a desire to break from conventional understandings about how video should be seen—and what kinds of spectatorial communities it might foster. If, as is often asserted, “video is now a primary tool in the construction of social space,” how might one unpack the different corporeal, political, and economic registers of this social space? 13 Portable video equipment had been available to artists since the 1960s—and marketed especially for artistic use, with an emphasis on the “mobility” and flexibility of production 14. Artists’ videos were integrated into museum shows almost immediately, sometimes featuring multiple monitors in sculptural arrangements (an aesthetic deployed most prominently by the so-called father of video art, Nam June Paik).15 The configurations Dorr proposes, however, depart from those models: here the viewing space would enwrap the audience on three sides with a series of different size monitors on casters that, ideally, would be moved during a scene. Rather than walking by or around the screen as in a gallery space, the audience in Dorr’s drawing sits in individual chairs (indicated by the grid of small squares). In an inversion of the usual dynamic, the monitors reposition themselves, while the audience is fixed. This is, in part, a cinematic or theatrical model rather than a video art one, with an audience clustered together and seated for a durational event rather than ambulating through a gallery installation that might include multiple monitors.

Dorr initially called this imagined space VideoVisions and doodled an accompanying logo featuring dual monitors from which a pair of eyes stare at the viewer: “VideoVisions wants you! Return the visual arts to the ARTISTS! Depose the Hollywood suck-pigs.” Dorr explicitly aligns his video screening space with the visual arts and as a direct counter to the hegemonic Hollywood film industry “suck-pigs,” a common trope in the West Coast countercultural video movement of the 1960s and 1970s. 16

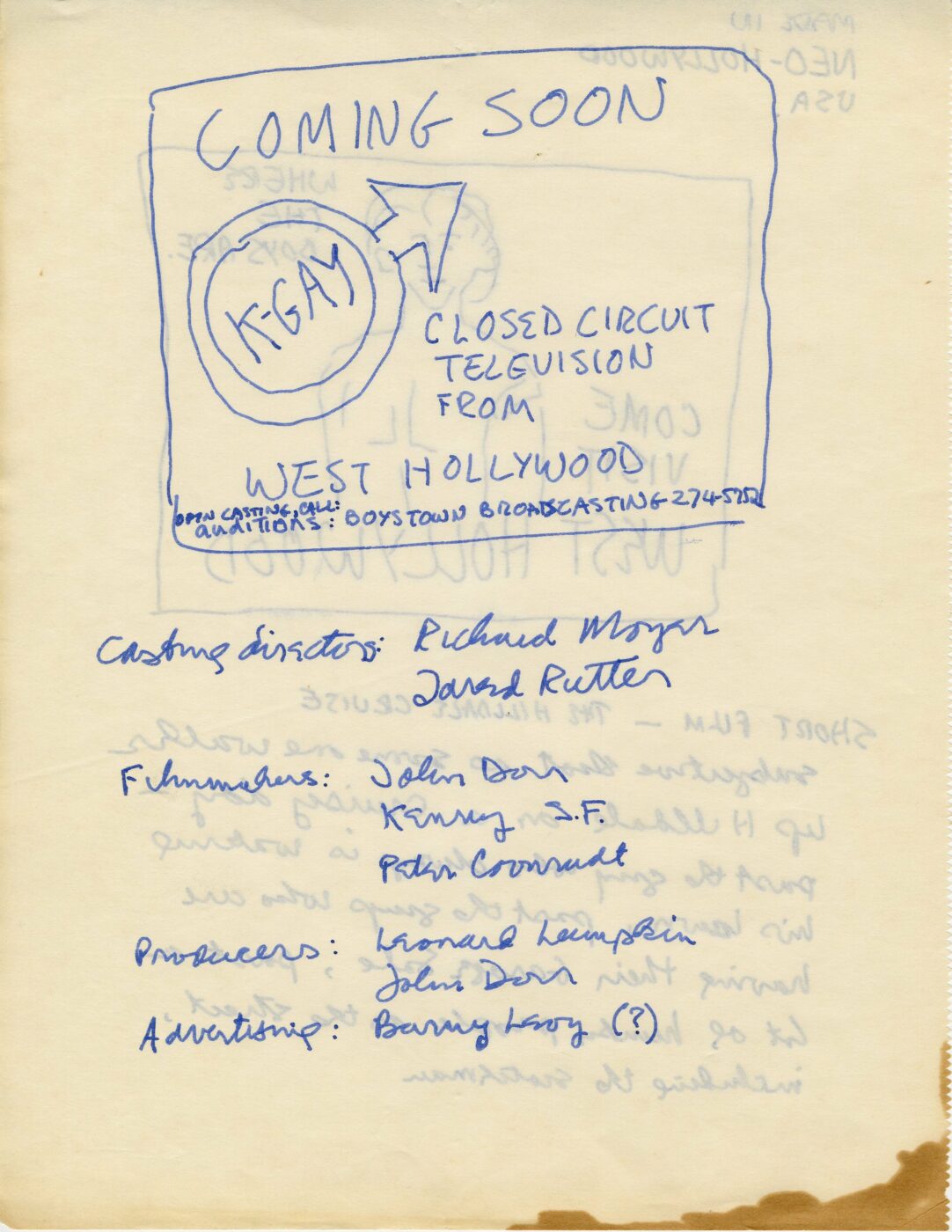

A sketch from the same journals retools the crude VideoVisions logo into something more matter-of-factly queer—KGAY, a name that suggests a queer television channel or radio frequency, the letters emblazoned inside a blocky arrow and encircled by an accompanying slogan, “Closed Circuit from West Hollywood.” Dorr used the margins of the same page to brainstorm ways to make KGAY a financially viable enterprise, including “sell ads to local merchants,” “sell tapes of the shows to people,” and “exchange an ad for video equipment.” With his schedule for two nightly showings at fixed intervals and plans for intermissions, he clearly was eyeing the cinematic, if not theatrical, show-time traditions of Davis’s “formal occasions.”

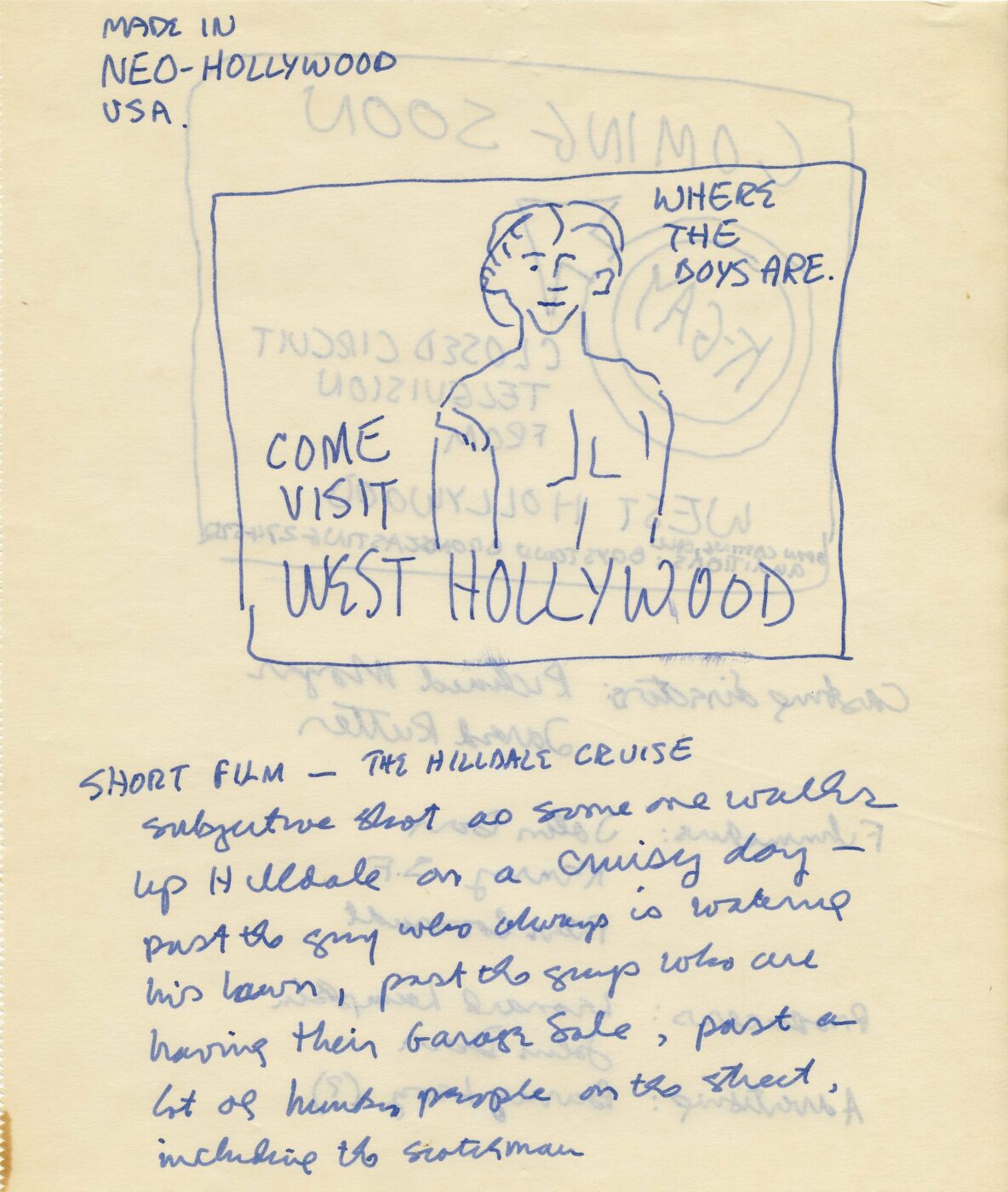

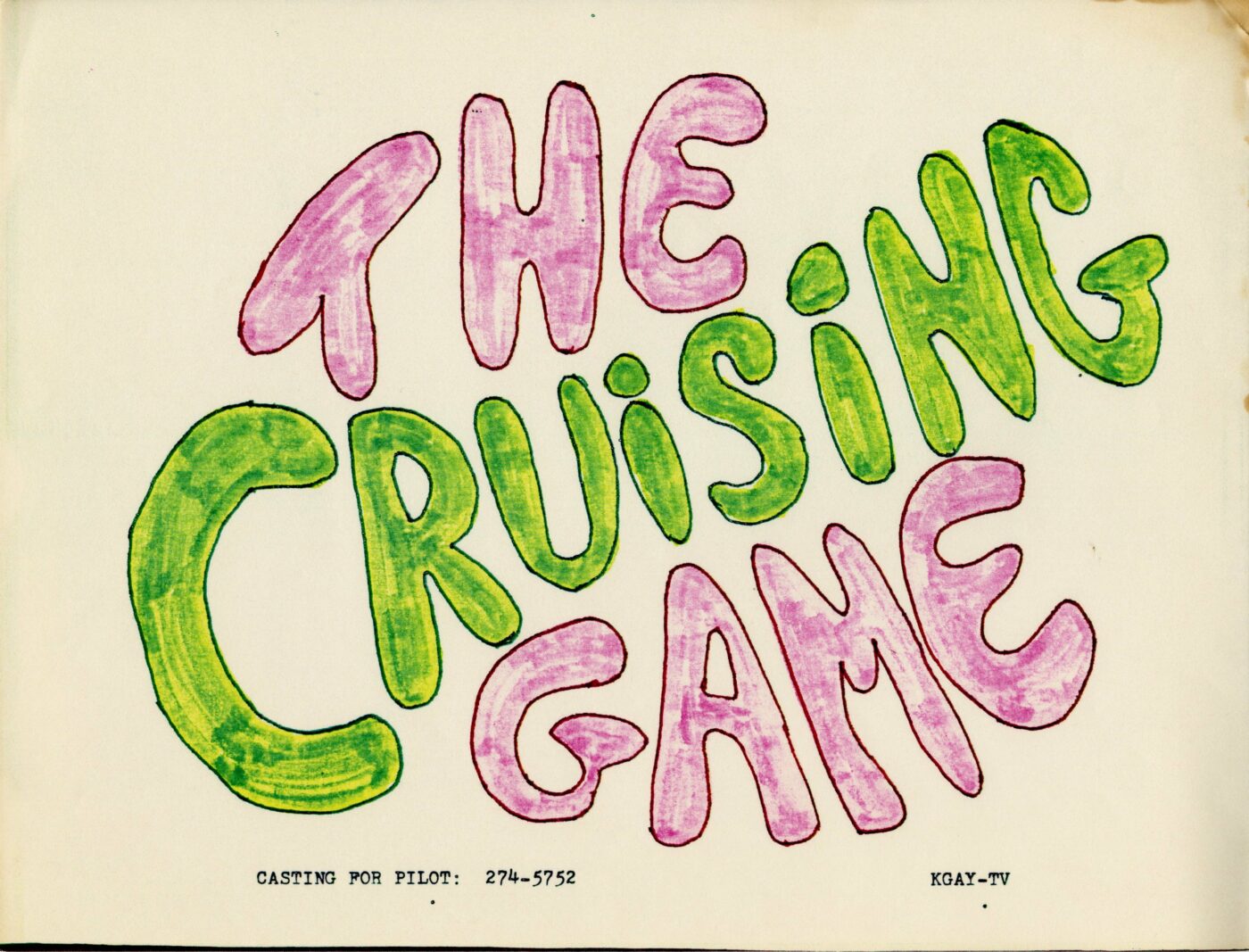

On another page, a further slogan appears: “Come Visit West Hollywood/Where the Boys Are.” Explicitly framing his project through the lens of queer space, Dorr here firmly locates his video microcinema in a particular location— West Hollywood, which was then just becoming what it is today, a Southern California site strongly associated with gay men. Dorr’s slogan includes a sketch of a man with tousled hair and chiseled chest muscles contained within the outline of a monitor, as if it is a screenshot of a televised ad. From the outset the center was meant to function both as a place to watch videos and a meeting point for gay male spectators, as Dorr invents a slogan that suggests not only media production but also imagines it as a neighbor- hood hub for queer cruising. Under this drawing, Dorr jotted down notes for a short film that takes cruising as its focal point. Called The Hilldale Cruise, the imagined piece would be a “subjective short as someone walks up Hilldale on a cruisy [sic] day, past the guy who always is watering his lawn, past the guys who are having their Garage Sale.” The short would capture the peripatetic wanderings of an unnamed protagonist as he has erotically charged chance encounters with the many gay men of a residential street in West Hollywood. When displayed for a largely queer audience who are also there to meet and mingle, the screening room would become the final stop of his “cruisy” tour. In the late 1970s, Dorr’s imaginative engine was fueled by the possibilities created when new technologies met queer sociability, especially gay male sex. Dorr brainstormed plans for a game show featuring “hunky cruisers” called “The Cruising Game” (though the telephone number at the bottom of this drawing indicates that he was ready to start casting for the pilot, the project was never realized) and imagined a “video sex magazine exchange club” in which members would swap their homemade porn tapes.

As with the name “VideoVisions,” Dorr’s catchy moniker KGAY did not last—he eventually settled on EZTV, because it suggested “easy-to-make television,” even though “TV” was a misleading shorthand, as EZTV was not in the end a broadcasting or televisual initiative. 17 In 1979, Dorr inaugurated screenings of independent videos at the West Hollywood Community Center and showed a range of locally produced media, including everything from fictional features to abstract formal experiments. This periodic colonization of a neighborhood space had its advantages and dis- advantages. Though the community center had ample seating, the municipal nature of the building might limit the amount of sexu- ally explicit material that could be shown. Ultimately, the screen- ings were such a success that Dorr realized he needed a permanent location, and, after inhabiting other sites, in 1983 he opened the full-time EZTV Video Center, expanding to a nearby strip mall on Santa Monica Boulevard, the main thoroughfare of West Hollywood, about a block west of La Cienega.

EZTV was widely considered “America’s first video theater.” Variety wrote, “EZTV has established itself as the showcase outlet for feature length independent productions shot entirely on tape.” 18 Dorr elaborated, “We are perhaps the first full-time space to offer a public outlet for the new body of work made possible by the revolution in low-cost video production.” 19 EZTV also rented equipment and provided editing assistance for any self-declared media-makers and encouraged every manner of independent production—they had a “policy of no policy.”20 From the outset, EZTV was run and operated by a core membership group of about twenty people, mostly gay men (as the early name KGAY indicates) but also including lesbians and a handful of straight men and women, as well as encompassing many other axes of diversity. People of color were central to every level of the organization, including James Williams (an openly gay African American photographer and video-maker who served as EZTV’s first curator of wall art) and Robert Hernandez (an out Chicano video artist who was one of EZTV’s early directors and a main funder).

Members of EZTV such as Tim Taylor were also at the forefront of confronting issues of physical ability and able-bodiedness. Taylor typed and painted with his feet due to childhood polio and made videos about disability. EZTV’s largely queer member- ship was not necessarily by design or part of its stated agenda, as it never marketed itself as “a queer video space”—rather, it reflected the makeup of its immediate locale. By furnishing low- cost technical support and an active audience, it became a pre- eminent early laboratory for queer video. (Many of the tapes created in the first years of EZTV have not survived.)21 However, a crucial aspect for its members was the fact that EZTV was not “identity based,” as so many other independent art spaces were defining themselves in the late 1970s. Despite the heavy presence of queer artists, the microcinema’s only self-definition was, according to one member, “the love of video and of artistic independence.”22

“Who Needs Hollywood!”

EZTV’s dedicated storefront included a small gallery, postproduction facilities that included editing suites, a studio for shooting with enough room to build small sets, and a screening room that sat up to forty (later expanded to one hundred), with lightweight chairs clustered around three monitors in a close approximation to Dorr’s original sketches. In the end, Dorr’s fantasy sketch of an intimate video spectatorship with mobile monitors was only partially realized. Several monitors were present, but, succumbing to technical limitations, they were stationed on pedestals—one in the front and two on the side—rigged to show the same image at the same time to maximize visibility no matter the position of the chairs and to partially enfold the viewers. In defiance of the reigning museum/gallery model for watching video art (in which work is looped and viewers wander in at random and catch what they can), EZTV screenings usually followed defined event structures. Evening programs generally started with shorts, followed by a feature (as with a movie, tickets were sold, usually costing a few dollars). Beginning in 1984, an opening montage designed by Mark Shepard preceded the screenings, bracketing whatever was shown as an EZTV experience. In the montage, the EZTV logo floats atop a variety of backgrounds, spliced together with incon- gruous clips from EZTV productions, while fast-cutting clips highlight the process of video production (hands push editing deck buttons or slide video cassettes into receptive slots).

EZTV insisted that it resisted the atomized model of viewing promoted by places such as the Long Beach Museum of Art, which was at that time the premiere institution for video art in the United States and was located some thirty miles south of West Hollywood. 23 Dorr and others in EZTV perceived the institution- alized “Long Beach model” as offering a limited, conservative view of the potential of video, because the museum space was best suited to short tapes that could be consumed by gallerygoers in a relatively brief amount of time, a method of viewership more aligned with looking at sculpture than watching a feature-length film.24

Far from opposing one another, however, EZTV and the Long Beach Museum can both be seen to partake of a postminimal rhetoric of video, in particular how it has been associated with the destabilization of a fixed, removed cinematic spectator. In her introduction to the exhibition Into the Light, on projected film and video in the 1960s and 1970s, Chrissie Ilses writes, “Building on Minimalism’s phenomenological approach, the darkened gallery’s space invites participation, movement, the sharing of multiple viewpoints, the dismantling of the single frontal screen, and an analytical, distanced form of viewer.” 25

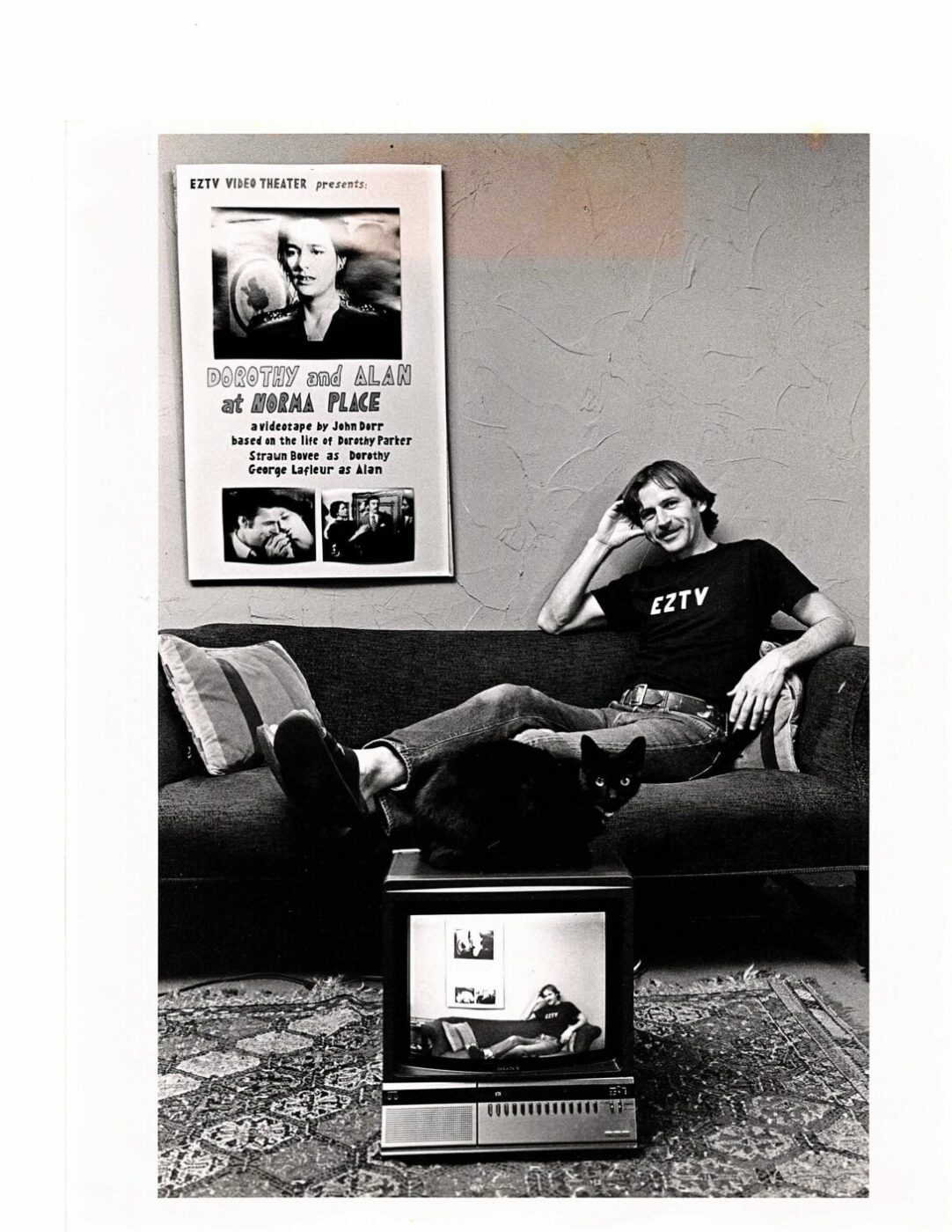

A photograph from a Los Angeles publication in 1982 shows the more casual, even quasi-domestic space that EZTV meant to promote, with Dorr pictured at home wearing an EZTV T-shirt lounging on a couch, with his cat on the video monitor on the ground (reflex- ively, the monitor shows a version of the photo in which it is depicted). This scene of staged coziness is meant to measure Dorr’s desired distance from the “white cube” viewing experience. Key to EZTV’s viewing structure was the fact that the audience was gathered together for a set duration. By taking monitors out of the home and making the viewing collective, one “went out” to see EZTV’s video and hence defied the prevailing wisdom about what happens to social relations when watching small screens. Jerry Mander’s popular book from 1978, Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, asserts, “Television encourages separation: people from community, people from each other, people from themselves, creating more buying units and discouraging organized opposition to the system. It creates surrogate community: itself.”26 For Dorr and others at EZTV, however, the group dynamic of attentive watchers and a common experience in front of the screen was crucial to their understanding that video brought people together to occupy shared space and create new spectatorial dynamics. Its screenings drew devoted audiences, which frequently consisted largely of other independent media- makers. One of EZTV’s most important functions was actively cultivating and summoning into existence an ever-changing community of viewers by creating a feedback circuit in which the work that was shown influenced the work that was made on-site. Many of the tapes shown during EZTV screenings were produced in its facilities. The venue’s rare combination of on-site editing and in-house screening made that feedback circuit at times very small, as work cycled quickly between the upstairs editing area and the downstairs theater area.

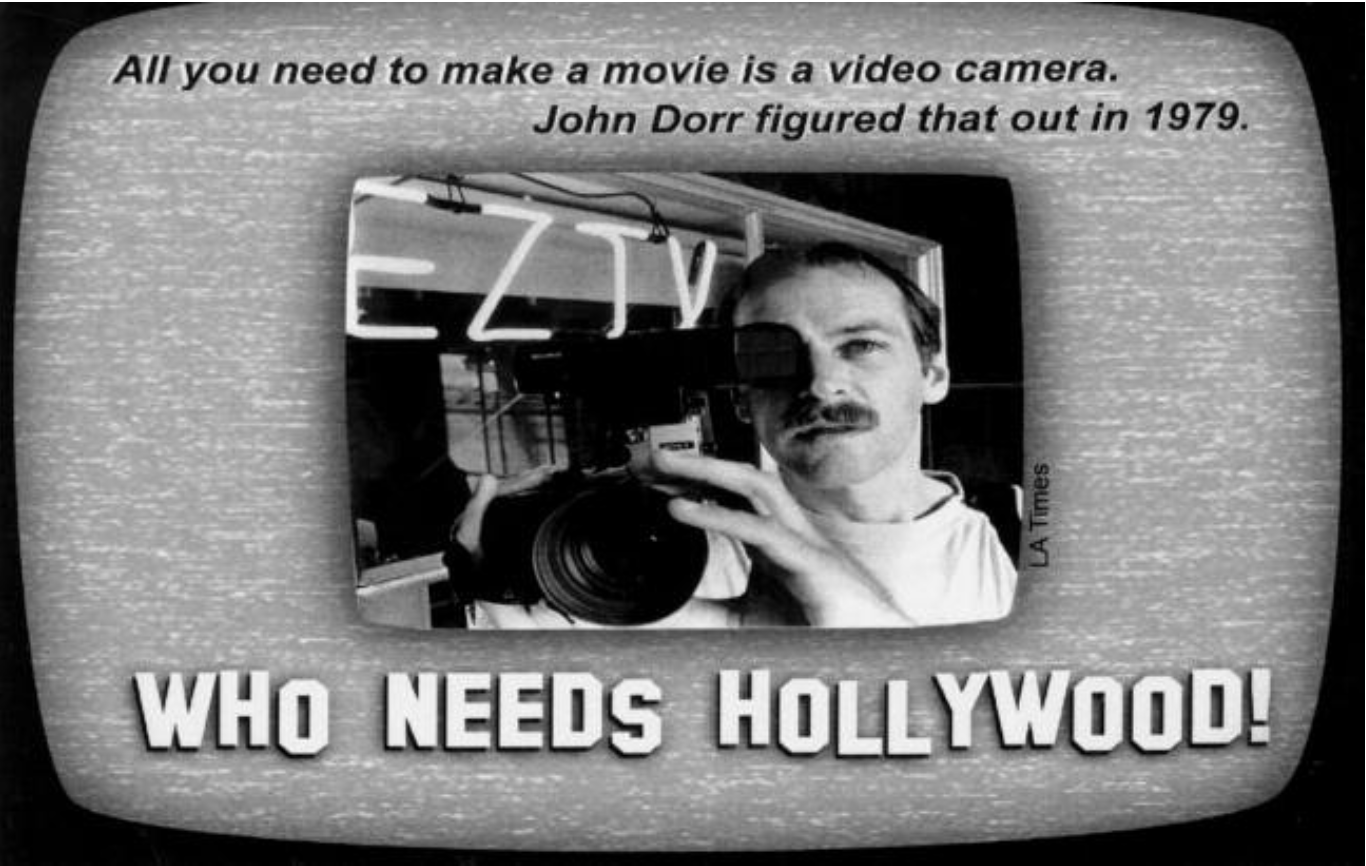

In its promotional materials, EZTV heralded a do-it-yourself approach to media-making that was meant to reject the high-gloss products of Hollywood, as in Nina Rota’s documentary about Dorr titled Who Needs Hollywood! “All you need to make a movie is a video camera. John Dorr figured that out in 1979.” A promotional postcard for the documentary features a photo from the Los Angeles Times of Dorr standing in front of the neon EZTV storefront sign with his camera pointing out at the audience as an implicit challenge to reject teams of editors, postproduction man- agers, and script-by-committee, embracing instead the scrappy ethos of single-camera work (EZTV rented out cameras at low cost). EZTV understood itself as expansive and pluralistic in its attempt to open up access to the video production process. However, as much as it dismissed Hollywood, it was also vitally physically adjacent to the culture industry in Hollywood and parasitically utilized some of its surplus resources. Film crews would come to EZTV after hours to make their own work and share skills. As one former member recalls, “some of Hollywood’s most hard-working character actors as well as producers, writers, and directors made EZTV their affordable creative haven.”27 Dorr noted that “equipment came in miraculously,” often through donation, as those involved in film production on all levels came to EZTV to make their own work after-hours. 28 In many ways, EZTV picked up and fed off of the resources of Hollywood; its relationship to mainstream media was not strictly counter- or anti-institutional but rather oppositional in the way that so much oppositionality is really about symbiosis. Who needs Hollywood? They did: Hollywood had to exist, symboli- cally but also materially, with its overproduction of talent and skill, to enable the growth of something like EZTV, which drafted off Hollywood workers’ excess time and cast-off equipment. Los Angeles is not just a company town with a monolithic movie culture and a singular art scene: its vastness and unruliness have made it an incubator for alternative modes of making that take advantage of proximity to the resources, publicity machines, labor, and rejects of mainstream media. Video-makers affiliated with EZTV were able to mobilize the talents, expertise, and abil- ities of underemployed Hollywood editors, technicians, camera operators, and actors.

Featuring Features

As one of the country’s first screening venue dedicated solely to video, ETZV was heralded by the national and local press as at the forefront of experimental independent media. 29 What was experimental about their work, however, was not always strictly formal, as it was often patterned on the systems of representation found in industrial cinema. In Who Needs Hollywood! EZTV narrates itself as being in the business of “movies,” an anomalous term for artists working with video in the late 1970s and 1980s, especially since so much contemporaneous video was explicitly constructed against the storytelling conventions of televisual culture and “movies.”30 By contrast, what Dorr championed, and what he himself made, was more overtly in dialogue with the gay plot- driven cinema of someone like John Waters (who also emerged in the 1970s), with his stylized, melodramatic thematizations of shock and schlock, than with video art. When interviewing Dorr in 1984, Rick Pamplin attempts to clarify the muddled terminology surrounding feature-length videos, saying, “I keep calling them films. Is there a term? Do you just call them video films?” 31 Dorr answered that he prefers the blanket term movies, which takes medium out of consideration and foregrounds the feature- length duration (it was more common to refer to work as “tapes” to maintain the discursive and technical distinctions between filmic and video practices). 32

From the outset, works made and screened at EZTV had a relationship to the queer aesthetics of camp. Dorr, who had attended film school and worked in film production, never positioned himself as anti-film but rather believed in the promise of popu- larization that has accompanied video technology since its inception—what Martha Rosler calls its “utopian moment”—not as a new form of television but as a cheap surrogate or accessible substitute for film.33

(…)

Extrait de Julia Bryan-Wilson, ‘“Out to See Video”: EZTV’s Queer Microcinema in West Hollywood’, Grey Room, n°56 été 2014 , pp. 56-66. © 2014 Grey Room, Inc. and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Tous droits réservés.

https://www.greyroom.org/issues/56/46/out-to-see-video-eztvs-queer-microcinema-in-west-hollywood/

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Rosler, “Video.”